Where Fire is a Treatment, GIS Helps Prescribe It

Across the US from the Southeast to the Mountain West and beyond, landscapes ranging from grasslands to forests need more than sun, soil and rain to thrive…they also need fire.

In the interest of public safety, complete fire suppression used to be the policy of many land management agencies across the nation, but decades of observation and research have shown that fire is an integral part of many ecosystems’ cycles of maturation and regrowth. Like the mythological phoenix, some plants simply need to burn, to start life anew from the ashes. The Table Mountain pine in the Appalachians, for example, relies exclusively on flame to open its cones and release its seeds. Longleaf pines on the Atlantic coastal plain need fire to keep other plants from overshadowing their seedlings.

Public safety remains a primary concern whenever fire is on the landscape. Now, some of the newest geospatial technologies are helping federal agencies to precisely and safely use fire to restore and manage the lands that need it to thrive.

Fire as a prescription

The National Park Service (NPS) Wildland Fire Management Program is one such federal entity that relies on geospatial tools to keep fire-dependent habitats healthy, by deciding where and when to recommend, and implement, prescribed fires.

A prescribed fire is one that is intentionally applied, under favorable weather conditions, to achieve specific management objectives. These objectives can include revitalizing fire-dependent ecosystems, maintaining culturally important landscapes, lowering the risk of future wildfire and more.

In the Southeast, some landscapes like those at Big Cypress National Preserve in Florida have a natural fire return interval of three to five years. If the area’s vegetation is not purposefully burned in that time, a potentially dangerous wildfire is essentially inevitable. Because fire managers choose where, when and how to set them, prescribed fires are low-risk and high-reward. Their flames burn cooler and lower than those of wildfires––and the area they cover at any one time is a targeted and more manageable size––while still providing fire-dependent ecosystems with the treatment they need.

To plan a prescribed fire, NPS personnel must have a deep understanding of fire behavior, but they also need to know a lot about the landscape’s fire history, sensitive habitat, the locations of valuable buildings and other structures that need protecting, and the availability of firefighting resources. And that requires geospatial data.

“Folks don’t just drop a match and set a prescribed fire. There are months and months of pre-planning that go into it. And there has always been a map involved,” says Justin Shedd, a research associate at the Center for Geospatial Analytics at North Carolina State University.

For over a dozen years, Shedd has worked with the NPS’s three eastern regions, the Northeast, National Capital and Southeast, on a wide range of Geographic Information System (GIS) based projects. Shedd specializes in applying geospatial problem-solving to fire management in the National Parks––from developing training materials that coach NPS staff through the technical details of data collection, to providing NPS administrators and management personnel with his expert insights about the possibilities and limits of geospatial data.

Location-based data are crucial to all aspects of fire management, he explains, including mapping active fires, assessing conditions post-fire and planning for prescribed fires.

“Fire managers used to walk an area and sketch on a paper topo [topographic] map” before the advent of computer- and web-based mapping software, Shedd explains. “Now, nearly everyone has a GPS unit and spatial data collection tool right in their pocket––a smartphone. That technology helps fire managers collect a lot of important spatial information on the fly, which they can then share with operations leaders and use for making rapid decisions.”

Geospatial tools as a prescription pad for fire

“Geospatial data and analysis have become commonplace, almost expected, in wildland fire management and land management,” Shedd says. Gone are the days when a simple spreadsheet provides needed answers to management questions. “If you want to know where and what, the best way to get that information is through geospatial analysis.”

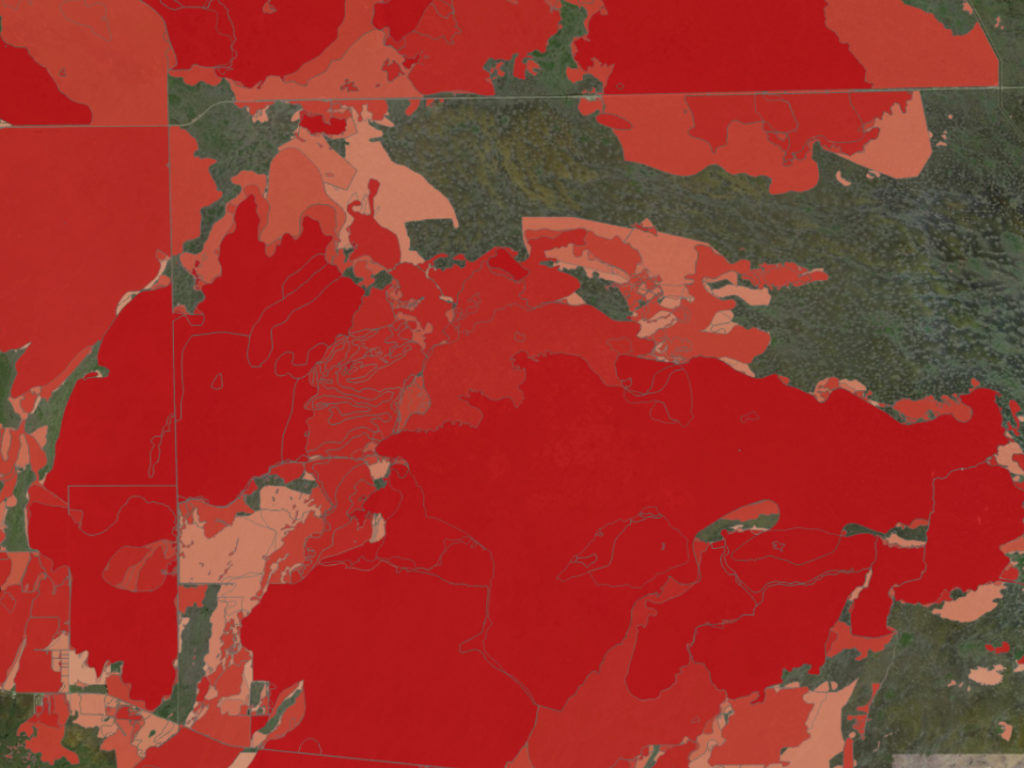

With location-based data about the extent and timing of past wildland fires and past prescribed fires, NPS fire managers can figure out which areas of a park are likely to have the highest “fuel loads”––e.g., flammable twigs, pine needles, dry grass––and therefore are most vulnerable in the event of an ignition. Those are the most logical places for a treatment of prescribed fire.

By examining the locations of recently burned areas, managers can also plan prescribed fires to fit together like puzzle pieces, protecting a larger continuous area by removing larger swaths of fuel and helping prescribed fires to extinguish themselves when they run out of material to burn. This strategy has been particularly successful at Big Cypress National Preserve, where strategic prescribed fires have continued to provide benefits for both natural systems and public safety for years after they were performed at the park.

And this is just one example of how GIS helps fire management planning.

Spatial data also indicate the locations of hydrants, existing fire breaks like roads and streams, and houses or other “values” that may be at risk, and can help fire departments make contingency plans in the event of wildland fire. For example, fire managers may use these data to determine the resources (equipment and personnel) that would be needed if an unplanned fire were to occur. In this way, geospatial tools can serve as “pre-support to plan for something that has not or may never happen,” Shedd says.

Spreading the word about fire

Firefighters in their bright yellow gear are often the most publicly visible people in fire management, but they are part of a large team who work both beside the flames and behind the scenes to ensure public safety and to reach management goals. “There’s a lot of good GIS work going on, and there’s a lot of good fire work going on,” Shedd says, “but you don’t usually hear about it. You hear about the catastrophic wildfire, the bad fire. But you don’t hear as much, if at all, about the good, prescribed fire.”

In the Southeast, the National Park Service has used prescribed fire to manage cultural landscapes and maintain and revitalize fire-adapted ecosystems for over sixty years, and “people are accustomed to it happening,” Shedd says. But they may not fully understand how it works or why it’s so important.

And so Shedd not only uses GIS to help NPS regional offices and individual parks to manage their geospatial data; he also uses GIS to help them spread the word about their fire-related activities.

“GIS is more than just maps,” Shedd says. “It facilitates communication and can allow you to make cool things, like a story map.” For the past two years, Shedd has created story maps that draw on a centralized database of spatial information to highlight specific fire-related events at parks in the Northeast Region and the Southeast Region. He also created a story map that tells, in-depth through text and visuals, a multi-year story of fire management at Big Cypress National Preserve.

“The story map really resonates with people,” Shedd says. “It ties text and photos and maps together, and there’s a lot of technical GIS stuff on the back end” that most people will never see, and don’t need to understand, to use and enjoy it. Unlike a formal report, a story map is interactive and can be easily explored on a mobile device. “It’s a different avenue,” he says. “You can look at it while you’re sitting on a plane or train or riding as a passenger in a car.” And anyone can access the story map using Wi-Fi or a data plan, because it all runs on ArcGIS Online.

“NC State was one of the pioneers of using ArcGIS Online to collect data related to fire management,” Shedd explains. “We’ve been able to push the envelope of what GIS can do in a management setting.”

At the Center for Geospatial Analytics, Shedd’s award-winning work has involved improving geospatial data sharing and communication among Park Service staff and their cooperators. Thanks to the work of geospatial professionals like him, GIS is helping fire managers across the country to decide the best course of treatment for landscapes that need fire to thrive.