First-Year Students Learn the Value of GIS for Environmental Justice

Location matters for addressing practically any environmental challenge: Wildlife depend on suitable habitat in specific places to thrive; pollution carried by rain from city streets flows into rivers downstream; and discriminatory policies have shaped the structures of neighborhoods and the circumstances of the people who live there.

For over five years, the Environmental First Year Program at North Carolina State University has taught students the importance of location to addressing environmental issues, as part of the foundational course ENV 101: Exploring the Environment.

“It takes a lot of creative and critical thinking to solve grand challenges,” said Megan Lupek, director of the Environmental First Year Program and instructor of the course. “Otherwise, they’d already be solved.” By partnering with experts from NC State’s Center for Geospatial Analytics, Lupek gives students the chance to think critically through a place-based lens. Over the course of a two-week case study, students use GIS (Geographic Information Systems) to collect and analyze their own data, exposing the impacts of institutional racism on environmental inequities in their own city.

Neighborhood as Classroom

Less than ten minutes’ drive from NC State’s Central Campus in western Raleigh lies the neighborhood of Rochester Heights, developed in the 1950s within the floodplain of Walnut Creek. The neighborhood is predominantly Black for historical reasons: In the early 20th century, the city demolished prosperous downtown Black neighborhoods, displacing 165 families, to construct new highways. Due to racially segregated housing policies and practices, homes were built in the Walnut Creek floodplain specifically for African Americans.

At the time, “it was illegal for Black people to live north of Edenton Street in Raleigh,” explained Stacy Nelson, a faculty fellow in the Center for Geospatial Analytics, professor in the Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources, and interim associate dean for diversity and inclusion of the College of Natural Resources (CNR). “Nobody wanted that land anyway, at the bottom of the watershed,” he said, because it frequently floods, and so families with limited options were the ones who moved in.

Every fall, students in ENV 101 visit Rochester Heights to learn about, and witness, the impacts of racist practices on environmental inequity.

In the hall of St. Ambrose Episcopal Church, where a local environmental justice advocacy group was founded in the 1990s, NC State alum Father Jemonde Taylor explains the history of Rochester Heights and how development elsewhere in Raleigh and Cary exacerbates local flooding. Students also learn about environmental justice more broadly from former CNR associate professor Louie Rivers III, now senior social science advisor at the US Environmental Protection Agency.

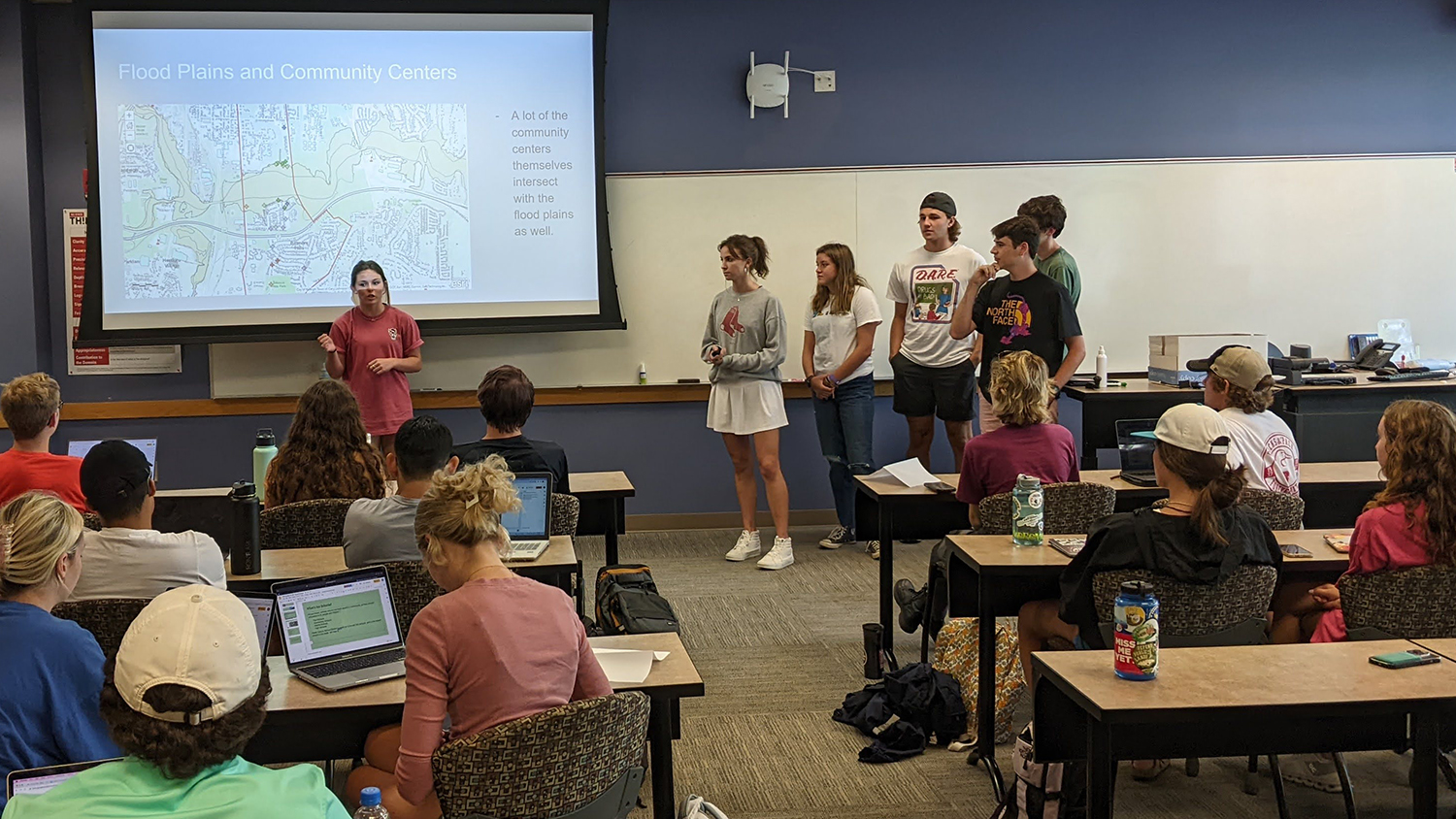

After talking with the guest speakers, students then walk the streets of Rochester Heights and nearby Biltmore Hills, two of the oldest historically Black neighborhoods in Raleigh, to collect “Quality of Life” data. Using the ArcGIS Collector app on their smartphones, each student records the locations of features related to an assigned metric, such as schools, community amenities like playgrounds, and goods and services like grocery stores and pharmacies.

Quite often, students don’t find what they’ve been assigned to look for. “No data or low data is important data too,” Lupek said she reminds them. “It’s telling.”

The area students walk represents “an older, Black neighborhood with limited voice and power to protect their property and investments” from flooding, explained Nelson. “That also affects goods and services and their connectedness to the rest of the community.”

Meaning-Making with Spatial Analysis

Back in their classroom at NC State, students then analyze the data they’ve collected to find spatial patterns and interpret what they mean.

Nelson gives students a primer on GIS so that they can work together in ArcGIS Online and share their findings with the entire class. Center for Geospatial Analytics research associate Bill Slocumb creates the databases students need to visualize environmental information about southeast Raleigh and run analyses with the data they collected. “Bill works tirelessly behind the scenes to make it work for us,” Nelson said. “There is really a tremendous amount of effort that goes into building these databases, sometimes 100 hours or more on the back end, to make it relatively easy for students to develop the necessary expertise in one sitting. Folks like Bill contribute their time and energy simply because we know how critical it is for our next generation to have the most advanced tools at their disposal to tackle our greatest natural and societal challenges. Getting things ready for the students is a lot of work each year, but worth it in the end.”

Working in ArcGIS Online is “really an opportunity for students to learn basic GIS skills but also to figure out, ‘how does my data actually relate to the environmental features of the landscape,’” Nelson explained. “We do a crash course in GIS, but the idea is that the maps they create communicate ideas, and they use those ideas to communicate about solutions.”

By visualizing which homes, schools and businesses lie within the Walnut Creek floodplain, and calculating walking distances and walking times between these destinations, students discover that flooding poses a risk to many buildings in the Rochester Heights and Biltmore Hills neighborhoods, and that many people live in “food deserts” without convenient access to grocery stores. Flood zones also make the availability of other stores and services unreliable.

“When the students analyze the data, they look through a lens of what they imagine an idealized neighborhood to be, based on their own experience or just basic human decency,” Nelson said. “They really get to ask themselves how the community relates to the data they collected, and think about the people who live in the neighborhoods they’ve mapped. How does a community go about their daily lives, get kids to school, when there’s flooding?”

With GIS, it quickly becomes clear to students that Raleigh’s history of discriminatory socio-economic policies and systemic racism have created real disadvantages and vulnerabilities still present in neighborhoods today. “Systemic racism has put people in the places where they are,” Nelson explained.

“Students are sitting in a place of privilege because they are at NC State,” Lupek added. “By far, the environmental justice case study comes up among the top for students, as the one they learned the most from and found most interesting.” In their final reflection papers, ENV 101 students often report having their eyes opened to the reality that environmental injustices exist not only in faraway places but also in the city where they attend college.

“It’s so cool to see the passion and energy that the students put into working together,” Nelson added. “We want them to think out of the box, a little broader, about how can you address these issues. These students are the ones to make substantive change. We want to instill in them that they have that power. They can fix things.”

Continuing the GIS Journey

ENV 101 introduces NC State freshmen to GIS because many environmental grand challenges require geospatial thinking. “Times have changed,” Nelson said. “If you’re dealing with natural resources, you have to have GIS skills. They are as important as any other skills. Over the last ten or twelve years, I can’t remember seeing any natural resources position that didn’t ask for GIS-related skills.”

“There are four ‘big things’ in geospatial science,” Slocumb added. “GIS, GPS [Global Positioning Systems], spatial databases and remote sensing. In this course, students are exposed to three of them.”

NC State currently offers three geospatial science courses specifically for undergraduates: GIS 205 (Spatial Thinking with GIS), GIS 280 (Introduction to GIS) and FOR 353 (GIS and Remote Sensing for Environmental Analysis and Assessment).

Since Fall 2017, 799 students have taken ENV 101; as of Fall 2022, 182 had gone on to take at least one geospatial science course (either GIS 205, GIS 280 or FOR 353), 20 had taken two geospatial courses, and one student had taken all three.

“The more we offer these courses, the more demand there is for more undergrad expansion in GIS,” Nelson said.

Bringing Lessons Learned into the Future

Overall, the goal of the Environmental First Year Program, and ENV 101, is to inspire NC State undergraduates to find their own unique path in environmental problem-solving. Growing as a student includes not only learning about a broad array of environmental topics but also learning from a variety of mentors.

“Megan Lupek intentionally tries to make sure that students see a diverse representation in the leadership of that course,” Nelson said, “so that they see a different perspective of the academic community that they are a part of.”

“Different perspectives are needed to tackle grand challenges,” Lupek said. “We definitely try to highlight diversity and that folks are coming from all different backgrounds.” She intentionally involves teaching assistants from underrepresented communities, and her students learn from many different community and campus partners who engage in the case studies.

In the environmental justice case study, ENV 101 students gain a deeper appreciation of varied backgrounds through their visit to southeast Raleigh and collaborative work using GIS. Explained Nelson, “Not only does this experience get the First Year students engaged in collecting data, and applying geospatial tools to make informed decisions about addressing these issues, but these students also gain an understanding of how to become better stewards of the environment and develop equitable solutions for all.”

- Categories: