Big Cats in the Backyard

Research conducted by a graduate student at NC State is shedding light on human-leopard interactions.

Known for its ability to go undetected by humans and wildlife alike, the leopard is one of the animal kingdom’s stealthiest species, staying out of sight by perching high up in the treetops or hiding in thick underbrush.

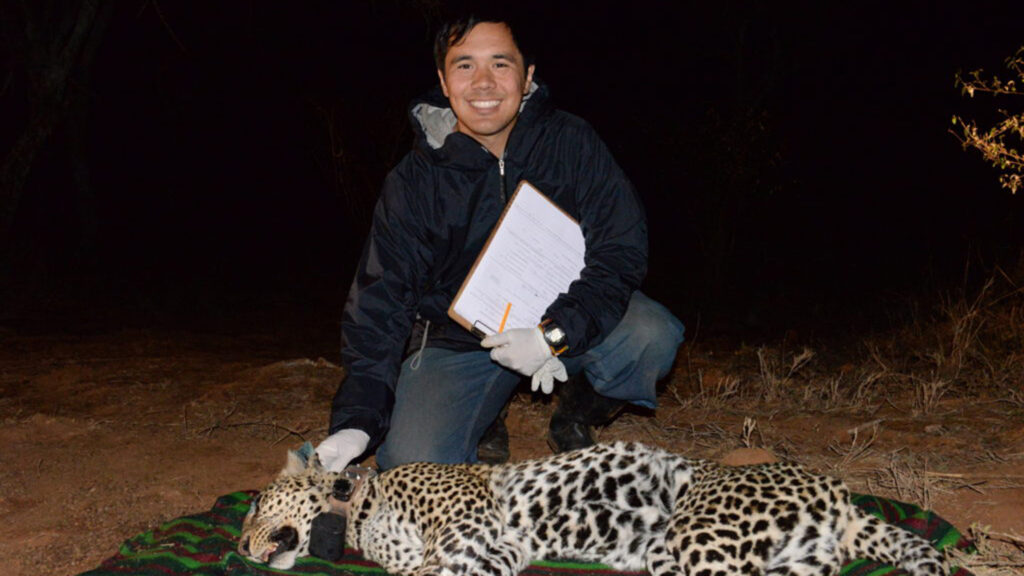

Yet, tracking the movements of these elusive creatures has become one of Matt Snider’s specialities during his time as a graduate student at NC State’s College of Natural Resources.

Snider, who recently graduated with a Master’s degree in Fisheries, Wildlife and Conservation Biology, has spent the last few years studying movement ecology in parts of Africa and Asia.

His thesis paper, “A Tale of Two Techniques: Leopard Collar Tracking and Mt. Kenya Camera Trapping,” was recently published and examines how leopard home range behavior is impacted by human population density.

“Human populations are having an increasing impact on wildlife populations, especially those species with relatively large home ranges since these animals are more likely to encounter anthropogenic disturbance,” Snider wrote. “Leopards are an ideal model for studying human impacts on wildlife space use, since they are clearly sensitive to human disturbance, occupying less than 40% of their historic geographic distribution, but are known to coexist with people in both high and low human density.”

Although the leopard is reclusive and spends most of its time alone, the species is highly adaptable and is the most widespread of all the big cats, with a historical range of about 13.5 million square miles across Africa, the Middle East and Asia. Unfortunately, like other large carnivores, the leopard is declining across its range and faces a growing number of threats, including habitat loss and conflict with humans.

Much of the leopard’s historical range has been converted to agriculture to produce crops for the growing human population, especially in Southeast Asia. This threat is expected to worsen in Africa over the coming decades due to growing economies, changing land tenures and increasing human populations.

Because leopards are opportunistic and typically require large home ranges, they are more likely to come into contact with human settlements and prey on livestock. Unfortunately, when this happens, farmers typically retaliate and kill the big cats in order to protect their animals.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) currently classifies the leopard as “vulnerable” to extinction and recognizes nine subspecies.

Snider said wildlife conservation on a landscape scale requires an accurate understanding of the ways in which habitats are used by resident mammals. Home range size provides insight into the habitat quality, animal density and social organization.

After compiling the tracking data of 76 individual leopards from ten research projects in seven countries, Snider uploaded it into the Movebank animal tracking database and compared leopard home range size with human population density, vegetative productivity, temperature, precipitation and habitat openness.

Snider’s analysis discovered that habitat type could modify the relationship between humans and leopards. While leopard home range size increased with rising human population density in closed habitats, it decreased with increasing human density in open habitats.

Regions with higher human populations, namely India and Kenya, had the smallest home ranges as these leopards lived in close quarters to humans while leopards in Namibia and Iran, where their home ranges were largest, either lived in relatively uninhabited landscapes or large protected parks.

Although leopards suffer from persecution by humans in some areas, it is possible that livestock populations are higher in open habitats, providing more food for leopards and allowing them to use smaller home ranges near people, according to Snider. In contrast, some leopards may persist in closed habitats around human population centers by consuming domestic species like dogs.

Snider said his analysis ultimately shows the potential for “broad scale comparisons across multiple studies to address large scale relationships in ecology.”

He added that future comparisons of leopard home ranges and human population densities could benefit conservation managers as they try to mitigate negative interactions.

“As landscapes become increasingly shared between leopards and humans, it is important to know which variables impact leopard behavior and how,” Snider wrote. “Recent work with the burgeoning leopard populations around human mega population centers, like Mumbai, may even hint that patches with high human-linked food resources could eventually become important leopard source zones as long as the density of their presence does not lead to local backlash.”

Snider plans to return to the College of Natural Resources to pursue his doctoral degree under the direction of Dr. Roland Kays, a research associate professor in the Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources. He will continue studying large mammal movement and landscape use.