Saving the Neuse River Waterdog

North Carolina's Rarest Salamander is Going Extinct. These Researchers Are Working to Save It.

With flame-like gills protruding from its head and black spots spanning the length of its slimy, mud-colored body, the Neuse River Waterdog is arguably one of North Carolina’s most charismatic species. Yet the giant salamander is on the path to extinction, a trend that NC State researchers are working to reverse before it’s too late.

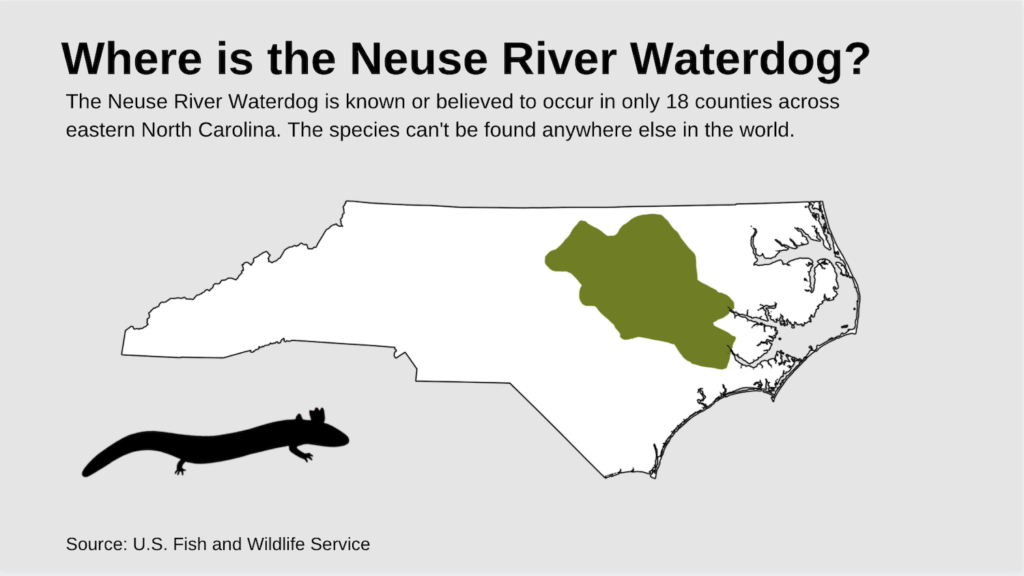

Found nowhere else in the world outside the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico river basins of eastern North Carolina, the Neuse River Waterdog is extremely elusive and seldom encountered in the outdoors, according to Eric Teitsworth, a doctoral student in the Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources at NC State’s College of Natural Resources.

“A lot of salamanders begin their life in the water as larvae and eventually move onto land. But this particular species never leaves the water,” he said. “They’re not easy to find.”

Because of its aquatic lifestyle, the Neuse River Waterdog has also largely evaded wildlife biologists looking to understand the species’ population health.

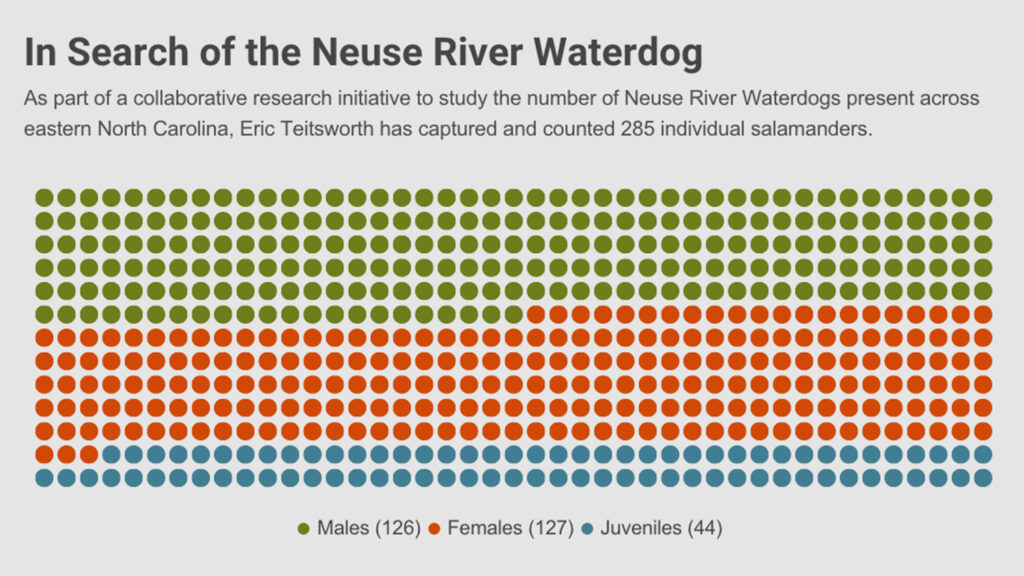

Teitsworth, working under the direction of Associate Professor Krishna Pacifici, is currently leading a coordinated effort with the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to determine the distribution, occupancy and abundance of the Neuse River Waterdog.

“We know the Waterdog has experienced significant population declines across its range, but we still don’t fully know how to protect this species. That’s what my research is trying to figure out,” Teitsworth said.

A Species on the Decline

In the early 1980s, the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences conducted a range-wide survey for the Neuse River Waterdog and found populations as far north as Durham and as far south as Greenville.

While the species is still fairly common in some of these places, the Neuse River Waterdog has seemingly disappeared from others, according to Teitsworth.

A range-wide population assessment conducted by the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission between 2011 and 2015 showed a 30-50% decrease in detections of the species in areas surveyed 30 years prior by the museum.

Teitsworth said the decline of the Neuse River Waterdog is concerning, because it is one of the region’s larger aquatic predators and helps to maintain ecosystem balance by preying on mollusks, insects and even small fish.

The Neuse River Waterdog is currently listed as a “species of special concern” by the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, meaning it cannot be legally killed, collected or possessed without a special permit.

Because of the documented population declines, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed to list Neuse River Waterdog as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act in May 2019. The decision has yet to be finalized.

Teitsworth said his research will ultimately help the federal agency create a “recovery plan” for the Neuse River Waterdog.

The Search for Answers

Currently, Teitsworth is conducting additional population surveys and working to find out why the Neuse River Waterdog is declining.

“By learning where Waterdogs can still be found and what their main threats are, we can implement the appropriate conservation measures,” Teitsworth said.

From December to March each year, when the salamanders are most active, Teitsworth visits various rivers and streams across eastern North Carolina to capture and count individuals. He also collects tissue samples.

Since 2015, Teitsworth has surveyed 130 locations. The preliminary results show that Neuse River Waterdog populations are actively declining in Craven, Durham, Franklin, Granville, Orange, Person, Wake, Warren and Wayne counties.

“I’m still conducting surveys, but the data I’ve collected so far suggest that some populations in the Neuse River around Raleigh and other parts of the Triangle have all but disappeared,” Teitsworth said. “You rarely find them there anymore.”

Teitsworth added that the Waterdog’s decline is likely a result of watershed instability and water pollution caused by increased rates of urban development and other factors.

Threats to Survival

North Carolina’s Triangle region — comprised of the cities of Raleigh, Durham and Chapel Hill — has experienced rapid growth over the past two decades and is expected to experience even more growth in the coming years. This growth will inevitably bring the development of additional housing complexes and roads, both of which can negatively impact water quality in nearby streams and rivers.

“Waterdogs prefer clean water that’s always flowing, and they’re very sensitive to change,” Teitsworth said. “When you have high rates of urban development, you get a lot of impervious surfaces that can increase the amount of water entering a stream after a storm. That can not only lead to increased variability in streamflow, but it can also cause increased sediment input that washes down and degrades habitat.”

Teitsworth added that large quantities of nutrient pollution, especially phosphorus and nitrogen, can also harm Neuse River Waterdog populations. This type of pollution results from fertilizers and animal waste that’s washed from lawns, urban developed areas, farm fields and industrial meat production facilities into streams and rivers.

While some of the same nutrients can be beneficial to aquatic life in small amounts, too many nutrients can contribute to excessive plant growth, algae blooms and low levels of dissolved oxygen in the water. The Neuse River Waterdog and other aquatic animals need dissolved oxygen to survive.

Teitsworth said organizations and government agencies can combat sediment erosion and nutrient pollution through various measures, including the implementation of riparian buffers and the remediation of wetlands.

Going forward, Teitsworth plans to continue his research in hopes of developing predictive occupancy models for the Neuse River Waterdog.

“Historically, a lot of surveys assumed Waterdogs were present at a particular location based on whether or not the researchers could catch any at all,” Teitsworth said. “But with occupancy modeling, we can predict where they are and where they aren’t. It’s a big step forward with regards to how we determine species distribution and habitat suitability.”

- Categories: