Building a Case for Community Gardens

As a community garden in Raleigh fights to remove regulatory barriers for commercialization, one NC State expert weighs in on the benefits of urban agriculture.

For centuries, farming has been a largely rural activity. But as rapid urbanization reduces access to food sources, city dwellers nationwide are growing plants and raising animals in and around their homes. This movement, known as urban farming or urban agriculture, is providing a wide range of health, environmental and economic benefits.

In North Carolina, a number of urban agriculture initiatives have sprung up in recent years. That includes the Well Fed Community Garden. Once an abandoned property in southwest Raleigh, the garden is now providing residents with local, organic produce — and some important lessons about how they’re food grows and why it matters, with the goal of reconnecting them to the environment and its many benefits.

It all began in 2012 when Arthur and Anya Gordon discovered a 1.5-acre property along Athens Drive. For decades, the couple had gardened extensively and purchased produce and meats from local farmers markets for their restaurant, the Irregardless Café. But with an increasing interest in sustainability and urban agriculture, the Gordons wanted to start their own “little farm” within the city limits.

“The property was about to be foreclosed, and it was completely overgrown with trees and shrubs. But we saw a lot of potential,” said Anya Gordon, who is a board member at the Center for Environmental Farming Systems, a partnership between NC State and other institutions aimed at promoting equitable food and farming systems.

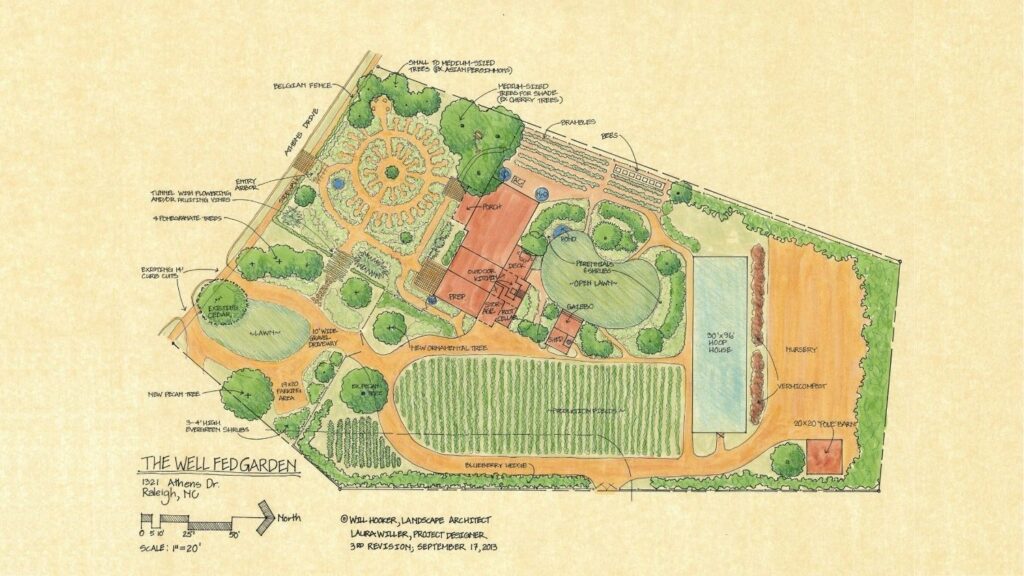

After purchasing the property, the Gordons applied for and obtained a permit from the City of Raleigh and hired Will Hooker, then a landscape architect and professor at NC State, to design a sustainable permaculture garden plan with fields and extension facilities for growing vegetables, fruits, mushrooms, herbs, flowers, and teas, as well as a pollinator garden to sustain beehives for honey and a chicken coop for egg production.

With help from the garden’s first manager, Jenn Sanford-Johnson, and volunteers, the Gordons slowly implemented the design and transformed the property into the Well Fed Community Garden — a name inspired by the discovery of an old well on the property, which reminded the couple of the biblical passage “re-digging our father’s wells” as well as of the food and wellness that the garden would provide for the neighborhood.

Over the years, Sanford-Johnson and other managers operated Well Fed as a for-profit garden, selling 80% of the annual harvest to the Irregardless Café and then donating the remaining 20% to volunteers and community members. In 2019, however, the Gordons sold their restaurant and decided to change the garden’s business model, renting it to Tami Purdue, owner and operator of Sweet Peas Urban Gardens in Raleigh.

Purdue, a 1982 alumna with a degree in accounting, spent nearly two decades as a legal administrator at Coats and Bennet, a law firm in Cary, before resigning in August 2014 to launch Sweet Peas Urban Gardens. With the ability to grow up to three tons of microgreens a year out of a 325-square-foot shipping container, Purdue has developed a successful track record in the world of urban agriculture, selling her bounty to more than 100 restaurants across North Carolina over the years.

Since partnering with the Gordons, Purdue has relocated her shipping container to the Well Fed Community Garden and now operates her microgreens enterprise from the property while also managing the garden’s fields and facilities. “Urban agriculture isn’t easy … it’s a 24/7 job. But it’s important,” Purdue said. “The garden not only increases accessibility to healthy food but also introduces people to the process of growing it.”

More Than Just a Garden

Urban agriculture — in particular, community gardening — has become increasingly popular in the 21st century, with the number of Americans growing food in community gardens rising by 200% between 2008 and 2016. And with good reason: The gardens provide a wide range of benefits, according to Sara Brune, a research associate in the Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism Management at NC State.

“As a result of agricultural industrialization, certain foods have become cheap and accessible for the majority of Americans. But it’s also had negative economic, social and environmental impacts,” Brune said. “Locally grown food promotes healthier eating, supports the economy, and helps protect the environment.”

Brune added that community gardens often implement sustainable practices aimed at preserving natural resources. At the Well Fed Community Garden, for example, Purdue uses crop rotation and companion planting for pest control, avoiding the use of pesticides that could pollute nearby waterways and cause greenhouse gas emissions.

“Locally grown food promotes healthier eating, supports the economy, and helps protect the environment.”

More importantly, community gardens can alleviate urban food deserts — geographic areas where residents aren’t able to access healthy foods, especially fruits and vegetables, because they must travel an inconvenient distance (greater than 1 mile) to reach a supermarket or grocery store.

Research shows that food deserts commonly occur in lower-income and minority communities, forcing residents to rely on unhealthy options such as processed foods from convenience stores, gas stations and fast-food restaurants. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s most recent food access report, about 39.5 million Americans, or 12.8% of the nation’s population, live in food deserts.

“There are more than 7 billion people to feed in the world and you can’t do it with community gardens alone,” Brune said. “But we need these gardens to balance food consumption, because they facilitate the access to low-cost, fresh produce for those who simply can’t get to it.”

While southwest Raleigh isn’t a food desert, there is only one grocery store, a Food Lion along Avent Ferry Road, located within a 1-mile radius of the Well Fed Community Garden, making it an important food source for the surrounding neighborhood. “I can easily feed the entire block from this property,” Purdue said.

The Well Fed Community Garden recently received permission from the City of Raleigh to establish an on-site farm stand, allowing Purdue to sell her produce to neighbors and others. Once the pandemic subsides, the garden will also continue to host events aimed at promoting urban agriculture. That includes gardening workshops, tours and more.

Brune, whose research focuses on the contribution of agritourism to local food systems, said that agritourism experiences increase people’s appreciation for local foods and local farmers. “Agritourism has long been perceived as an income diversification strategy for family farms. But our research shows that it’s far more important,” she said. “We’re finding that people are more willing to buy and advocate for local food after engaging in agritourism experiences.”

She added that the hands-on agricultural activities offered by community gardens such as the Well Fed Community Garden may play a similar role in shaping peoples’ preferences for local food in the urban context. “This indicates that apart from expanding the access to fresh food, community gardens may also strengthen local food systems by increasing the participant’s appreciation for local food and their likelihood to advocate for local food.”

It’s Not Easy Being Green

Despite the benefits provided by urban agriculture, community gardens still face various challenges, including zoning regulations and a lack of support from city governments. In 2013, the City of Raleigh officially adopted regulations for urban agriculture, including community gardens, as part of its Unified Development Ordinance.

The ordinance was designed “to preserve, protect and promote the public health, safety and general welfare of residents and businesses,” according to Cindy Holmes, the city’s assistant sustainability manager. But for many people, including Purdue and the Gordons, the ordinance is prohibitive to the commercialization of their community gardens.

When restaurants shut down during the onset of the pandemic, Purdue and the Gordons decided to sell directly to customers from a farm stand and applied for a permit from the city. To their surprise, the city denied their request, citing a rule in the UDO prohibiting community gardens from selling their products in residential zoning districts.

“We were essentially told that we weren’t allowed to sell on-site and that we’d have to go to a farmers market,” Purdue said. “I’ve sold my produce at several farmers markets for years and it’s not easy or efficient. You have to prepare on Fridays and then get up early on Saturdays to cram all your stuff in three or four cars.”

After being denied a permit, Purdue teamed up with Jenn Peeler Truman, an architect and local urban agriculture advocate, to create a citizen petition requesting a text change in the UDO that would allow farm stands in residential zoning districts. She presented that petition before the Raleigh City Council in August, capturing the attention of Mayor Mary-Ann Baldwin who requested a plan on how the council could change the text.

In March, the City Council finally approved the text change, removing the requirement for a special use permit in order to set up a farm stand at a community garden. The council also removed a regulation prohibiting community gardens from aggregating and selling products from other farms and a regulation prohibiting roadside signage.

However, despite these changes, community gardens must still seek approval from the city before installing farm stands. In April, Purdue submitted an application to the city for permitting. Again, to her surprise, it was denied, with the city quoting the former ordinance prohibiting farm stands. She is now appealing the decision.

Once approved, Purdue plans to install a farm stand and signage near the entrance of Well Fed Community Garden where she will sell her produce as well as products from other farms across the Triangle. “What’s so great about the UDO change is that it benefits all community gardens,” Purdue said. “But there’s still some other things that the city needs to change in order to better support urban agriculture.”

Collaborating with other community gardens and urban agriculture initiatives in Raleigh, Purdue recently presented additional requests to the council. That included a request for the city to incorporate a zoning allowance for hoop houses and other urban agriculture structures in residential districts, with the goal of making it easier for community gardens and similar operations to install these structures.

At the Well Fed Community Garden, Purdue has operated several hoop houses — a plastic-covered structure that allows for the growth of crops all year round — since 2015. In January, however, Purdue was cited by the city for not obtaining a building permit for the structure. While hoop houses and other accessory structures are allowed in residential districts throughout the city, they are subject to zoning requirements and require the issuance of a building permit if they exceed 12 feet by 12 feet.

Holmes said the city recognizes the benefits of urban agriculture, providing grants and free compost for community gardens. “Urban agriculture is a supportive action for the community and city to address both equity and resilience.”

She added that urban agriculture was recently included in the city’s Community Climate Action Plan as a strategy to preserve green space. The city is also exploring the potential use of its undevelopable surplus property for temporary or permanent use as community gardens as part of its updated strategic plan.

“The strategic plan teams are also looking to identify barriers and opportunities where the city can support the continued growth of urban agriculture on private property within the community,” Holmes said.

Purdue, though, hopes that support comes quickly. “We’ve had plenty of people from the city who support us and want to help out. But they can’t because the rules are outdated,” she said. “The time is right for this change to happen. I might be dead by the time it’s finished but at least it will be finished.”