Open Space Has Increased in the Triangle, But There’s Still Work To Be Done

Every spring, around 160 great blue herons and great egrets gather in the treetops above a beaver pond along Ellerbee Creek in northeast Durham to build nests and raise their young. This area is one of the birds’ only nesting sites, or “rookeries,” in the Triangle region of North Carolina. It’s also one of the region’s biggest success stories of what can happen when organizations come together to protect open space.

The Durham City Council voted to designate the pond, along with more than 200 acres of surrounding wetlands, as a “dedicated nature preserve” through the Natural Heritage Program last year, ensuring permanent protection by the state of North Carolina. It came as a result of a measure proposed by the Ellerbe Creek Watershed Association and the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources.

Sydney Case, a former graduate research assistant at the NC State College of Natural Resources, highlighted the creation of the Ellerbee Creek Dedicated Nature Preserve in a recent report about open space protection in the Triangle, writing: “This partnership is considered to be somewhat historic for the region … the preserve along with the partnership is a promising start to further endeavors.”

Case published the report, “The State of Open Space,” in May 2024. Her report calls attention to changes in population, land use and protected open space since 2000, and the need for continued focus on land conservation. It marks the first report of its kind to be published since 2000 and 2002, when the Triangle Land Conservancy released similar reports about open space protection in the region.

What is open space?

Open space is land left intentionally as fields and forests while other land is developed into homes, businesses and roadways, according to Case. Some examples include parks, greenways, farms and nature preserves. These spaces can provide a number of benefits, including habitat for native plants and animals, water quality protection, flood prevention, farming and forestry, recreation and a sense of place.

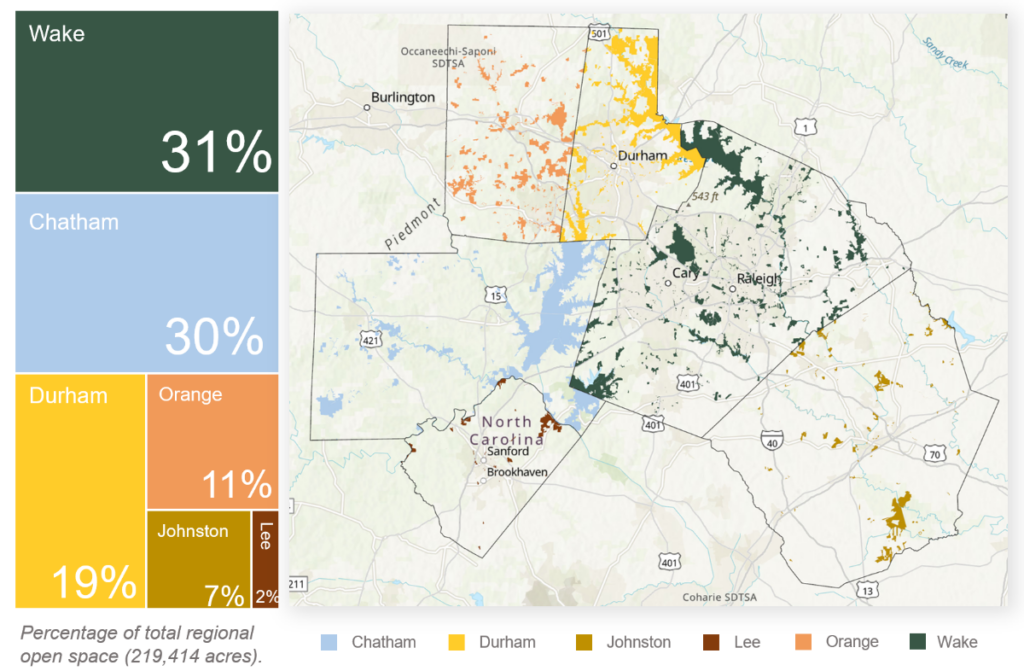

Triangle governments and conservation organizations have spent millions of dollars over the past two decades to protect open space. Protected open space in the six-county region increased by about 50% from 146,068 acres to 219,414 acres between 2000 and 2023. Wake, Chatham and Durham counties have the largest amounts of protected open space, respectively, followed by Orange, Johnston and Lee counties.

Unfortunately, the protection of open space in the region hasn’t kept up with population growth and development. The Triangle’s population increased 71% from almost 1.2 million in 2000 to over 2 million as of 2022, with Wake County experiencing the largest increase of about 547,175 people. Meanwhile, the area of developed land across the region increased by 24% from 394,818 acres in 2000 to 487,817 acres in 2021.

The goal of designating 30% of the world’s land and water as protected has long circulated as a target for conservation efforts. In the Triangle, Wake and Durham counties have officially adopted this goal. As of 2023, protected open space comprises only about 10% of the region’s total land cover. Triangle counties would need to protect more than 400,000 additional acres of open space to meet the 30% target.

“Even though progress has been made since 2000, population growth and development are increasing more quickly than open space protection [in the Triangle],” Case wrote in her report. “Along with being outpaced by population growth, the current protection rates reveal a long way to go in terms of meeting ‘percent protected’ goals.”

Case suggested that open space protection in the Triangle might benefit from improved data management strategies. The currently available data used for tracking open space protection in the Triangle doesn’t reflect the fact that some spaces, despite receiving some level of protection, remain vulnerable to reversal or future development. It also doesn’t include information about the management purpose of each space.

In her report, Case proposed a categorization schema that divides protected open space into permanently protected, well protected and least protected so that regional stakeholders can “visualize the Triangle’s open space on a degree of protection rather than visualizing the space assuming each parcel held the same type or strength of protection.”

The “permanently protected” category consists of open spaces protected by easement, legislation or state ownership, including state parks and preserves. The “well protected” category consists of open spaces protected for conservation purposes or those managed by city or local governments, including parks and greenways. Finally, the “least protected” category consists of all other remaining open spaces, ranging from educational land and learning centers to correctional centers and critical habitats.

About 55% of the protected open space in the Triangle is permanently protected, while 15% is well protected and 30% is least protected. Case said she hopes that her report will encourage conservation organizations, municipal planners and other regional stakeholders to collaboratively discuss inconsistencies in their data so that they might better track the progress of open space protection going forward.

NC State professor George Hess, who currently serves as chairman of Wake County’s Open Space and Parks Advisory Committee, supervised Case’s work on the report and agreed with her assessment, adding: “I hope what people take away from the report is that the Triangle has made a lot of progress in open space protection. But the other key message is that we’ve got to keep working on it. We can’t stop.”