Machine Learning and Satellite Imagery Could Help Protect the World’s Most Important Crops

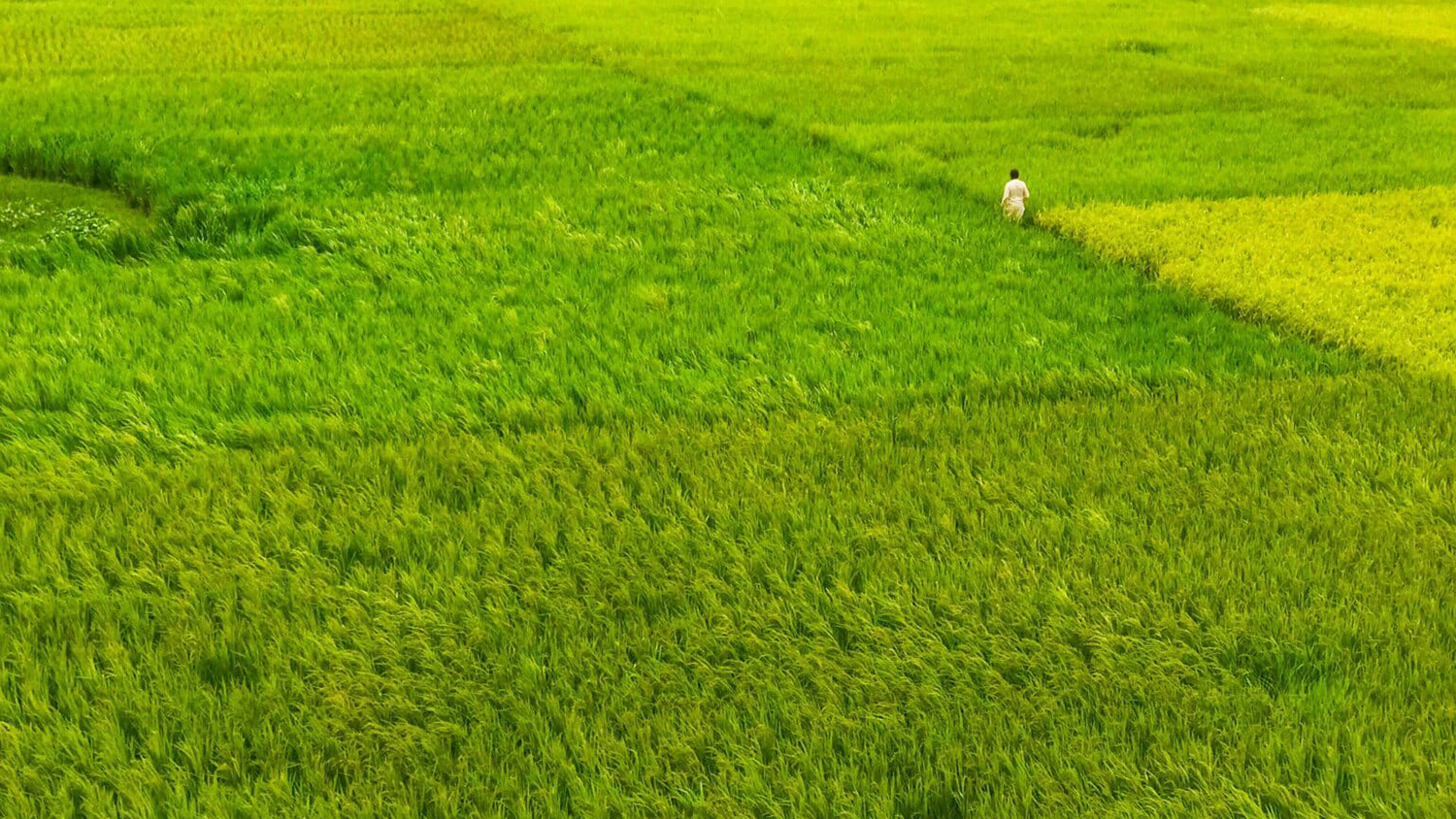

A new North Carolina State University study combines satellite imagery with machine learning technology to help model rice crop productivity faster and more accurately. The tool could help decision-makers around the world better assess how and where to plant rice, which is the primary source of energy for more than half of the world’s population.

The study focused on Bangladesh, which is the world’s third-largest producer of rice. The country is also the sixth most-vulnerable country in the world to climate change, as the destruction of rice crops by flooding has led to food insecurity.

Traditional crop monitoring techniques have not kept up with the pace of climate change, said Varun Tiwari, a doctoral student studying geospatial analytics at NC State and lead author of the study.

“In order to estimate crop productivity, people in Bangladesh use field data. They physically go to the field, harvest a crop and then interview the farmer, and then build a report on that. It is a time consuming and labor-intensive process. Additionally, the method adds inaccuracies when rice yield estimates are based on only a few samples rather than data from all fields, making it challenging to upscale to a national level,” Tiwari said. “What that means is that they do not have this information in time to make decisions on exports, imports or crop pricing. It also limits their ability to make long-term decisions like altering crops, introducing climate-resilient rice varieties, or changing rice cropping patterns.”

Researchers used a series of images of the same location recorded at regular intervals – known as time series satellite imagery – to measure vegetation and growth conditions, crop water content and soil condition at those locations. By combining that satellite data with field data, researchers trained their machine learning model to more precisely estimate rice crop productivity for the period from 2002 to 2021.

“With this model, we can see for instance that one area is doing well and another area is not doing as well as it needs to. If we have a highly productive area, we can decide to build more storage capacity in that area or invest more in transportation there,” Tiwari said. “Because that information is available much earlier, it gives decision-makers enough time to make good choices on how to allocate their resources.”

While the model is in the early stages of research, results have been positive. Accuracy has ranged between 90-92 percent with around 2 percent uncertainty, which refers to the model’s margin of error. When developed further, the model could be adapted to different kinds of crops in varied landscapes, Tiwari said.

“Bangladesh was the ideal place for us to begin, as 90% of the population includes rice in their daily diet. Agriculture, primarily rice cultivation, contributes around one-sixth of their national GDP. It’s very important for them to have these estimates right, and that was a demand we could fill,” Tiwari said. “If we can get similar data sets from other regions, we can apply this same framework there. Whether it’s the U.S, India or an African country, we want this method to be reproducible.”

This research was a collaboration between stakeholders, researchers and policymakers. In addition to NC State, organizations such as the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center, and the Bangladesh Rice Research Institute were involved to ensure the use of the best scientific practices for informed decision-making.

The paper, “Advancing Food Security: Rice Yield Estimation Framework using Time-Series Satellite Data & Machine Learning,” is published in PLOS ONE. Co-authors include Kelly Thorp, Mirela G. Tulbure, Joshua Gray, Mohammad Kamruzzaman, Timothy J. Krupnik, A. Sankarasubramanian and Marcelo Ardon.

Funding for the study comes from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and USAID through the Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia and the CGIAR Regional Integrated Initiative for Transforming Agrifood Systems in South Asia.

This article was originally published on NC State News.

- Categories: