Federal Funding for Research Fuels Innovation in Natural Resources

The College of Natural Resources receives millions of dollars in federal funding every year to support research and innovation aimed at solving urgent challenges at the intersection of the environment, economy and society.

In 2024 alone, the college’s faculty received nearly $22 million in competitive research grants from federal agencies, including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Forest Service, National Science Foundation, NASA, Environmental Protection Agency, and others.

“Federal funding is the backbone of our research enterprise,” said Robert Scheller, the college’s associate dean for research. “No other institution is capable of the sustained investment necessary for world-class research that the federal government provides.”

Scheller, also a professor in the Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources, added that while some faculty receive research funding from foundations, corporate sponsors and other sources, nearly all rely on some kind of federal funding.

That not only includes competitive research grants but also capacity funding, according to Scheller. Capacity funding refers to grants distributed by the federal government to land-grant universities in support of research and extension activities.

“Capacity funding represents a long-term investment in research programs that align with our land-grant mission to support the broader public, in North Carolina and beyond,” Scheller said.

In addition to providing financial resources necessary to invest in research facilities, equipment and personnel, capacity funding supports professional development, research partnerships, outreach initiatives and much more.

Capacity funding is especially crucial to fostering a climate for innovation, according to Scheller. It allows faculty to focus on developing novel research ideas, with less of an emphasis on traditional research metrics such as publishing in scientific journals.

Whereas competitive grants award limited funding to researchers based on a rigorous review process that evaluates the merit and potential impact of their proposed research, capacity funding is allocated to institutions annually based on predetermined criteria or eligibility rather than a competitive selection process. This provides predictability and stability for institutions, allowing them to plan and implement programs with greater certainty.

“Capacity funding allows us to make investments in research that wouldn’t otherwise be possible,” Scheller said. “Some research requires longer-term planning and execution — such as long-term field monitoring — or they focus on applied research that is more relevant to local economies — such as is produced by extension specialists.”

The federal government largely issues capacity grants to provide “baseline support” for research areas deemed essential to society, Scheller said. “They want us to continue investing in these areas, regardless of the success of one grant or faculty member.”

Capacity Grants at Work

Since 1962, for example, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has administered capacity grants through the McIntire-Stennis Cooperative Forestry Program to support forestry research and graduate education programs at land-grant institutions across the country.

McIntire-Stennis program funds are distributed to each state based on a formula that considers the non-federal commercial forestland area, the annual timber harvest volume, and total non-federal forestry research expenditures.

The College of Natural Resources has received McIntire-Stennis funds since the program was established. It receives about $1.1 million each year to support research and extension efforts that bolster North Carolina’s forestry industry, which contributes more than $40 billion to the state economy annually and provides approximately 152,000 jobs.

The college distributes awards to faculty through an internal competition. Projects that receive support from the McIntire-Stennis program are limited to a maximum of five years. The program currently supports more than a dozen research projects led by faculty from all three of the college’s departments and the Center for Geospatial Analytics.

Nils Peterson, for example, is working with several of his colleagues from the Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources “to measure the value of wildlife management areas in the southeastern United States and to identify land parcels best suited for protection in future wildlife management areas.”

North Carolina currently has about 94 wildlife management areas, which encompass some 2 million acres of public and private lands across the state. These areas protect wildlife, provide ecosystem services and generate income for rural communities through hunting, fishing and other recreational activities.

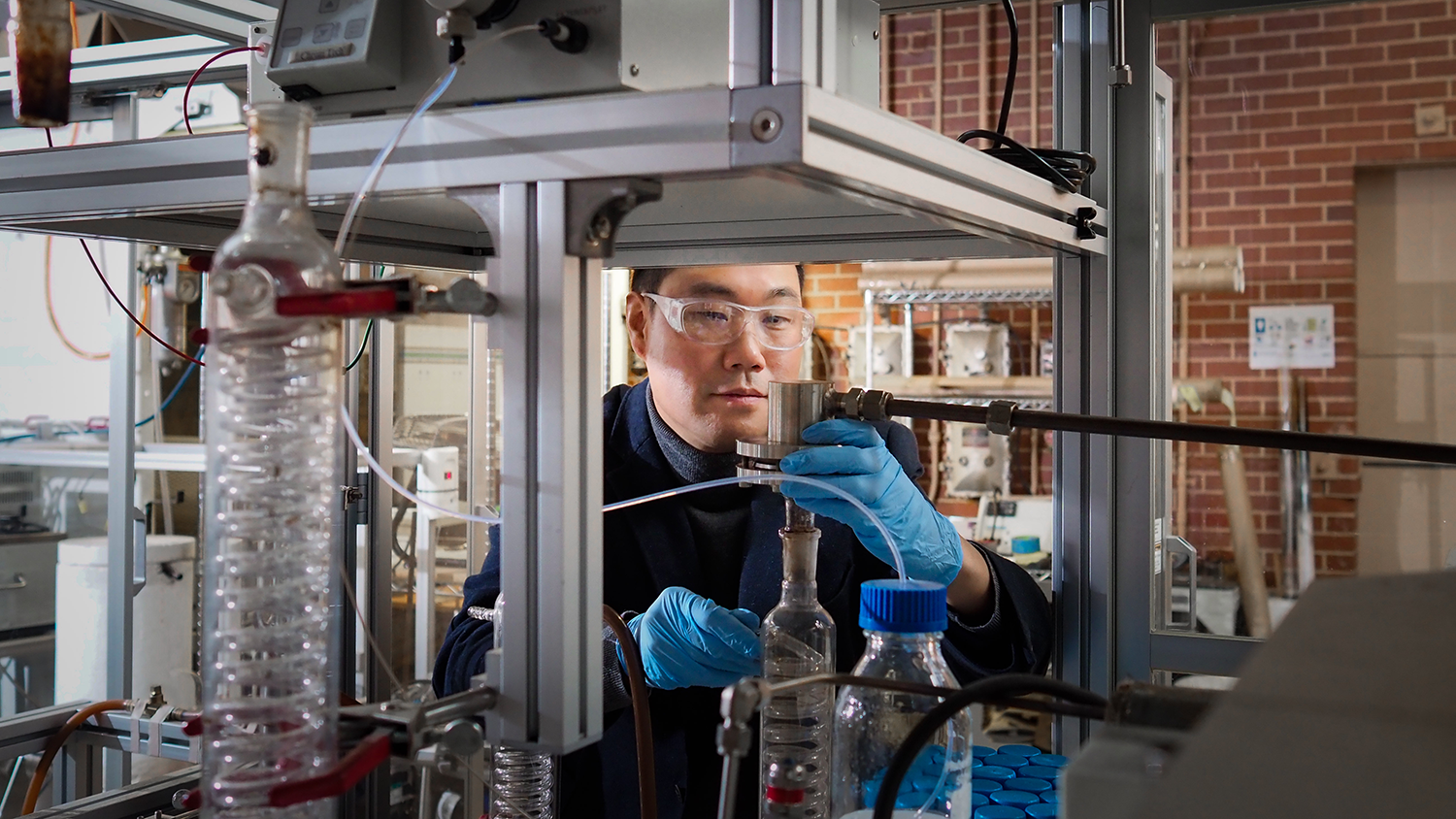

As part of another project, Nathalie Lavoine and Melissa Pasquinelli from the Department of Forest Biomaterials are working “to advance the commercialization of forest and agricultural resources as raw materials for the development of high-value-added food packaging with improved properties and new functionalities to replace single-use plastics.”

Single-use plastic food packaging, including containers and wrappers, don’t decompose naturally and can accumulate in landfills and oceans where they can contaminate soil, water and the food chain. But packaging made from wood and agricultural crop residues can be both biodegradable and recyclable, offering sustainable alternatives.

The McIntire-Stennis program, along with other capacity funding opportunities, not only support research but promote collaboration with community and industry partners. In her project to understand how regeneration harvests affect carbon storage in mixed-oak forests, for example, Jodi Forrester is working with scientists from the U.S. Forest Service’s Southern Research Station.

By partnering with different institutions and other organizations, the college’s faculty gain access to a wider range of expertise, resources and perspectives that can lead to more comprehensive and innovative research. Additionally, partnerships can help translate research findings into practical applications and policies for real-world challenges.

Capacity funding also supports the next generation of natural resources scientists, according to Scheller. Justin Whitehill and his collaborators, for example, are using McIntire-Stennis funds to train a graduate student to apply molecular technologies to help develop genetically-improved Fraser fir and loblolly pine trees — two species crucial to North Carolina’s forestry industry.

“Graduate students are the beating heart of our research. They are the primary research labor force. And after they graduate, they go on to deliver science to federal, state, university and even corporate institutions, benefiting society as a whole,” Scheller said.

Scheller concluded by stressing the importance of the continued support for capacity funding programs. “Capacity funding fills the gap left by competitive funding. If we are going to continue to serve the broader community of North Carolina — including farmers, foresters and landowners — we need capacity funding.”

- Categories: