Getting in Touch to Stop an Epidemic

On the West Coast of the U.S., a forest disease called sudden oak death is spreading, and land managers are on a mission to contain it. Forestry and Environmental Resources Ph.D. student Devon Gaydos and her team of collaborators are now using geospatial analytics to help those managers predict where the disease is likely to spread and which interventions might be most effective.

“We’ve been developing an interactive disease simulation model that allows stakeholders to test different management scenarios,” Devon says. “Until now, it’s mainly been used as a research tool, but this modeling framework has the potential to facilitate discussions between different stakeholder groups and to inform solutions for real-world landscape-scale problems.”

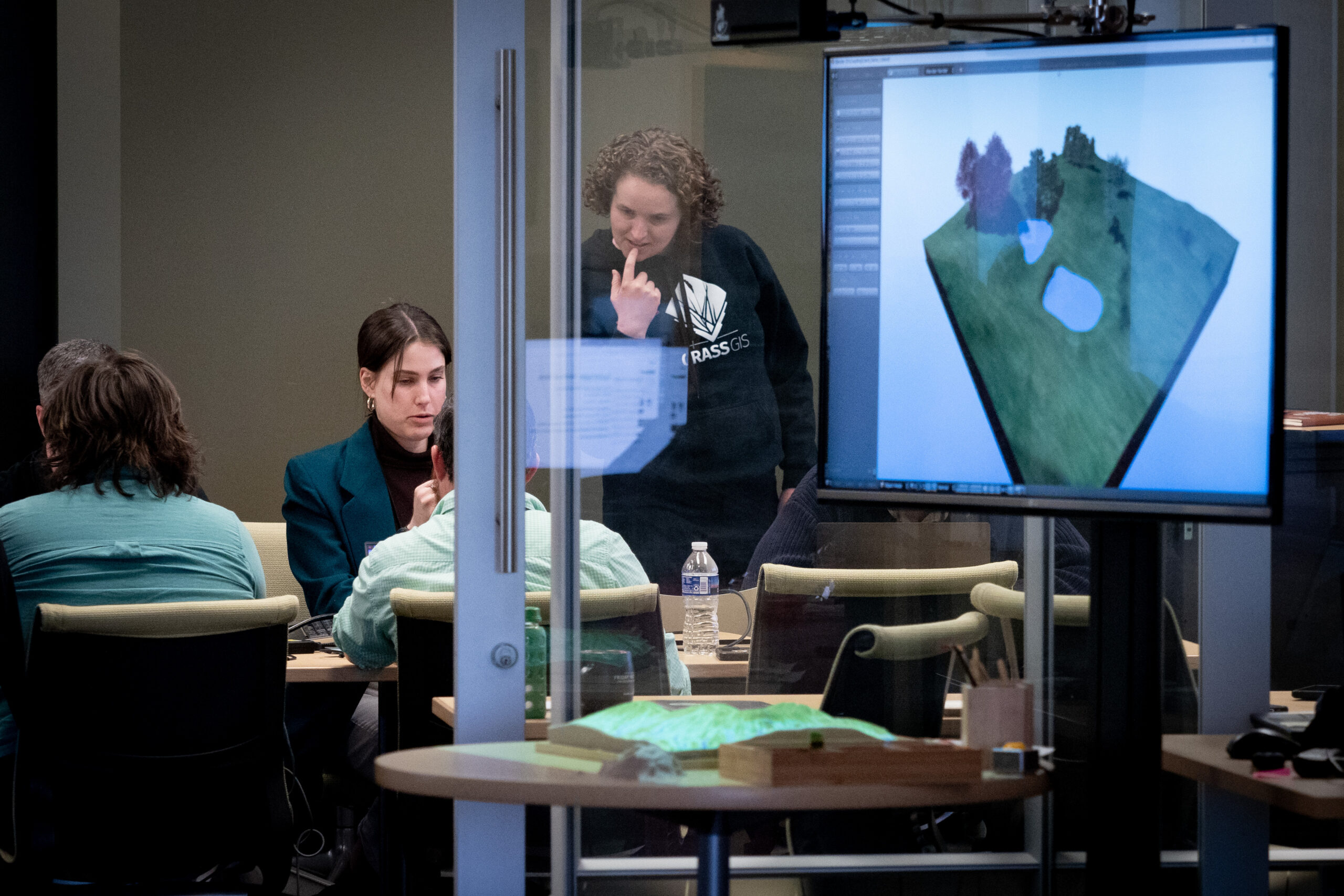

Advised by Ross Meentemeyer, director of the Center for Geospatial Analytics and professor in the College of Natural Resources, Devon is working with other students in the center to engage West Coast stakeholders in decision-making through Tangible Landscape––a system that weaves interactive simulations with a user-friendly interface that is responsive to touch.

A proof of concept published last March showed how center researchers were able to use Tangible Landscape to effectively roleplay sudden oak death management on a modeled landscape of California’s Sonoma Valley. Last month, Devon and her team debuted the model for use outside of the lab, flying to Curry County, Oregon, to conduct an on-site workshop with a group of stakeholders highly invested in sudden oak death management in the region. The group included foresters, forest pathologists and epidemiologists from the Oregon Department of Forestry, Oregon State University and U.S. Forest Service.

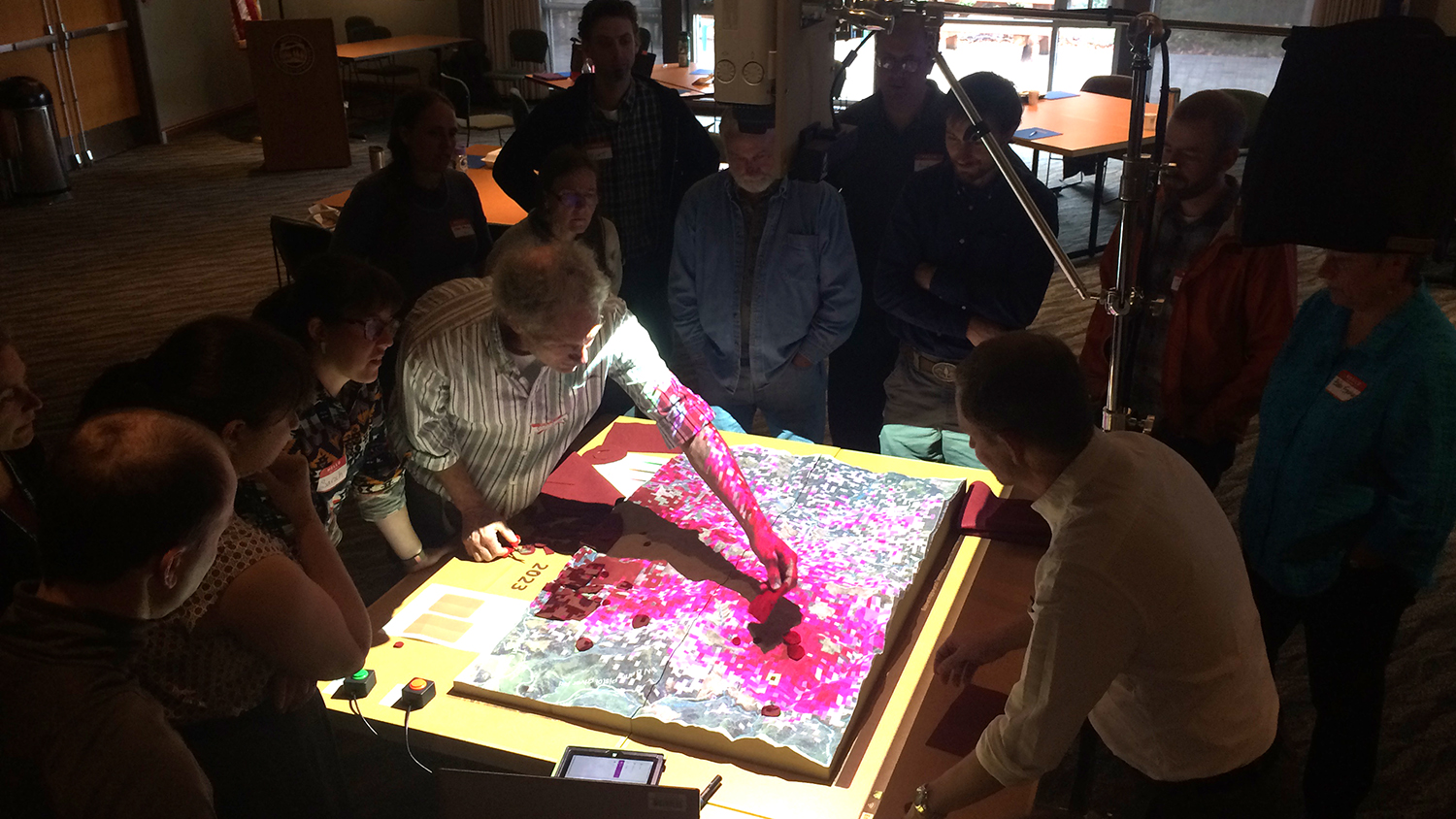

At the workshop, the dozen attendees gathered around a card-table-sized model representing a 12-km by 8-km area of land within Oregon’s sudden oak death quarantine zone. They were then challenged to select areas for management—that is, removal of host trees—to curtail spread as much as possible within a five-year timeframe, with varying levels of potential funding. Particularly important was protection of nearby Coos County, where a future quarantine could restrict export of timber, fruits and cultivated plants from a major international port. An online dashboard kept track of each player’s choices in this serious game and encouraged discussion among all the players.

As participants experimented with the model, they had room to be creative. One player arranged management on the landscape in a way that was “nothing we’d thought of before,” Devon says. Attendees provided helpful feedback for model improvement as well as reported how the system could be useful in their own work: from identifying where to conduct aerial surveys for dead trees, to determining funding needs and educating regional landowners.

“Our main goal was to demonstrate the model and get feedback from everyone,” Devon says. “That feedback is going to be used to improve the model so that we can use it in the future with other stakeholders and in different locations.” For example, Devon plans to return to Oregon to conduct another workshop next summer, this time with timber companies, private citizens and federal and state landowners.

“Engaging stakeholders with Tangible Landscape makes it possible to put sophisticated models at everyone’s fingertips without a steep learning curve, because hands-on interaction is very intuitive,” Meentemeyer says. “This is a game changer. And we could do so much more. We’re only scratching the surface.” Involving stakeholders in research and collaborative decision-making is a hallmark approach at the Center for Geospatial Analytics, and Meentemeyer welcomes additional partnerships. “When students and other researchers from the College of Natural Resources and beyond partner with the center, we’re able to accomplish things that no one ever dreamed of.”