NC State Professor Wins Prestigious Fellowship to Study Indigenous Rights

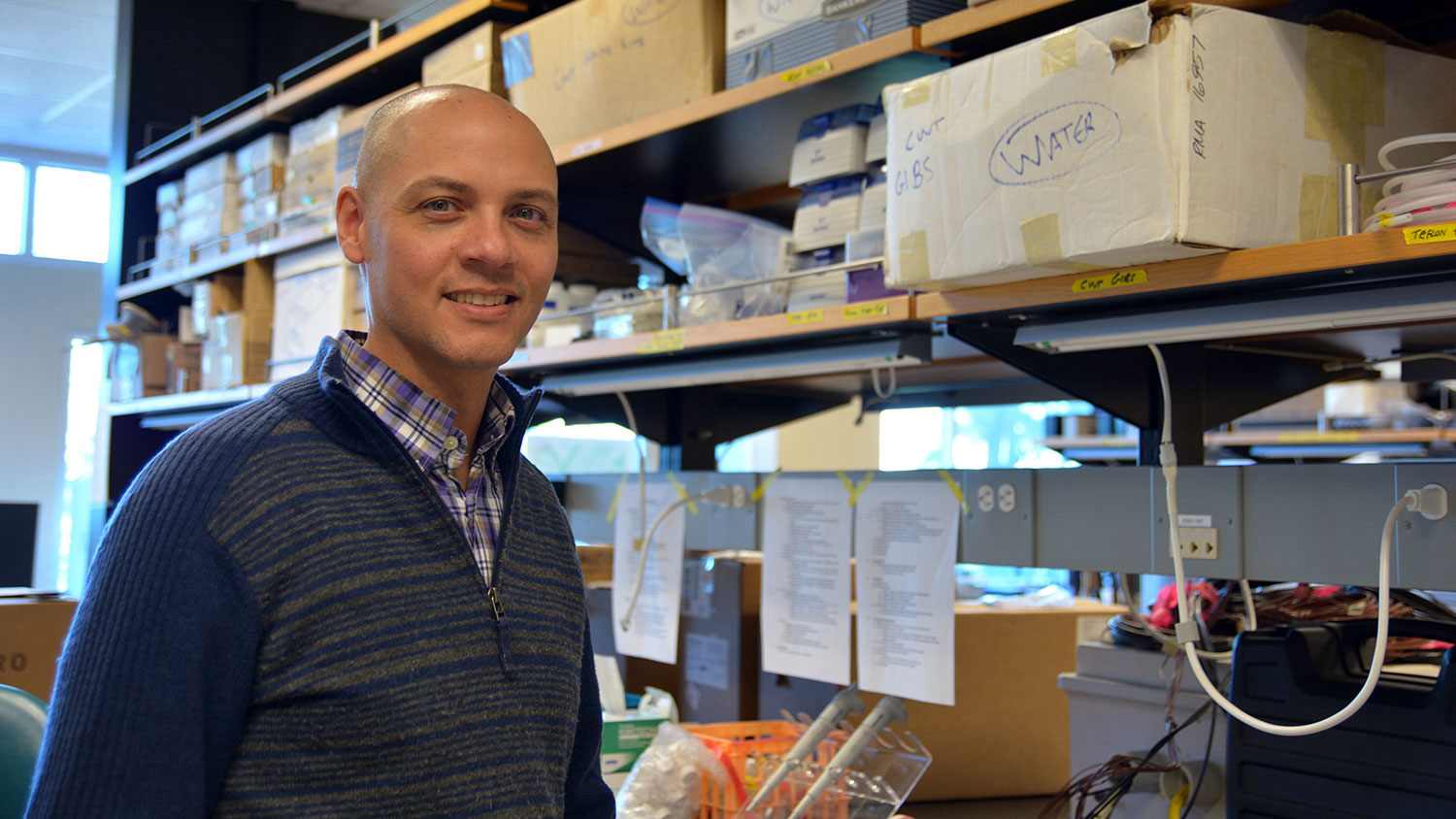

Ryan Emanuel, an associate professor and faculty scholar in the Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources at NC State’s College of Natural Resources, has been awarded a residential fellowship from the National Humanities Center.

Emanuel, who leads the department’s ecohydrology and watershed science research group, is one of only 33 fellows selected from 673 applicants. He is also the only faculty member at NC State to receive a fellowship from the center this year.

The National Humanities Center is the world’s only independent institute dedicated exclusively to advanced study in all areas of the humanities. Governed by a distinguished Board of Trustees from academic, professional, and public life, the Center began operation in 1978 and offers programs to encourage excellence in scholarship, improve teaching, and increase public appreciation for, and engagement with, the humanities.

“I’m honored to be selected as a fellow,” Emanuel said. “Few scientists have opportunities to pursue scholarship in the humanities, and I’m grateful for the chance to spend a year at the center focusing on interdisciplinary work that also has deep personal significance.”

Beginning in September, Emanuel will spend a year at the center’s campus in the Research Triangle Park to write a book about his research project, “Water in the Lumbee World: Environmental Justice, Indigenous Rights, and the Transformation of Home.”

The book, which is set to be published by UNC Press, will explore how the Lumbee Tribe and other Indigenous communities of eastern North Carolina preserve and expand their environmental knowledge of the region as they face increasing pressure from climate change, flooding and fossil fuel infrastructure projects.

It will also highlight the challenges and opportunities faced by Indigenous communities in the areas of environmental justice and sovereignty, with Emanuel analyzing the evolving role of Indigenous knowledge in the decision-making processes surrounding land-use, water quality and other contemporary environmental issues.

“I hope to lay out an academic argument for stronger policies surrounding environmental justice and Indigenous rights,” Emanuel said. “These are buzzwords to many people — especially after high-profile cases like Flint, Michigan and the Dakota Access Pipeline came into public consciousness. However, environmental justice and Indigenous rights are important concepts that intertwine with the histories and cultures of Lumbee and other Native American people.”

In addition to his hydrology research, Emanuel, who is an enrolled member of the Lumbee Tribe, studies policy issues surrounding environmental justice and Indigenous rights, working alongside tribal governments and Native American organizations in North Carolina to provide information and analysis related to environmental and cultural issues.

My goal is to help tribes and Indigenous organizations gain seats at the table for decisions that affect their people and their environments.”

Many of the state’s Indigenous communities — and their cultures — are intrinsically linked to their surrounding landscapes and riverscapes, imbuing them with a deep, placed-based knowledge of the region’s environment, according to Emanuel. But Indigenous knowledge is often excluded in the decision-making process with regards to activities that affect environmental and cultural resources within tribal territories, despite being a proven tool in promoting sustainable development and natural resource management.

A case-in-point is the proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline, a natural gas pipeline that’s slated to run 600 miles between West Virginia and eastern North Carolina. The pipeline is expected to cross several streams that feed into the Lumber River, a place of great cultural significance to the Lumbee Tribe, and disturb wetlands that house cultural resources.

Federal policies require agencies to solicit the participation of tribal governments when projects may impact ancestral land, as well as identify and address environmental justice issues during formal assessments and reviews of projects such as the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. But federal regulators largely ignored best practices for tribal engagement during the environmental review process for the pipeline, according to Emanuel.

Emanuel’s most recent efforts have focused on improving tribal engagement with federal agencies in the decision-making processes surrounding the pipeline.

“My goal is to help tribes and Indigenous organizations gain seats at the table for decisions that affect their people and their environments,” he said. “Eventually, I hope we will go beyond sitting at the table and will be leading these discussions. But for now, I think that I can help build strong partnerships between native nations and all types of institutions, including universities and government agencies, in ways that make it easier for tribes’ voices to be heard.”

Dr. Erin Sills, the Edwin F. Conger Professor of Forest Economics and Associate Head of the Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources, said Emanuel’s upcoming fellowship at the National Humanities Center is a testament to the quality and scope of his research agenda.

“He serves as a mentor and a role model for other faculty and students who aspire to do socially-relevant research that responds to the needs of the most vulnerable communities in our state,” she said. “We are fortunate to have him as a member of our department.”