Is It Too Late to Save the Amazon Rainforest?

NC State expert Erin Sills explores what the future holds for an ecosystem that faces record deforestation rates.

Though the Amazon rainforest covers less than 2% of the Earth’s surface, it plays a vital role in stabilizing the global climate, with its more than 390 billion trees storing massive amounts of carbon dioxide — a greenhouse gas that’s driving climate change.

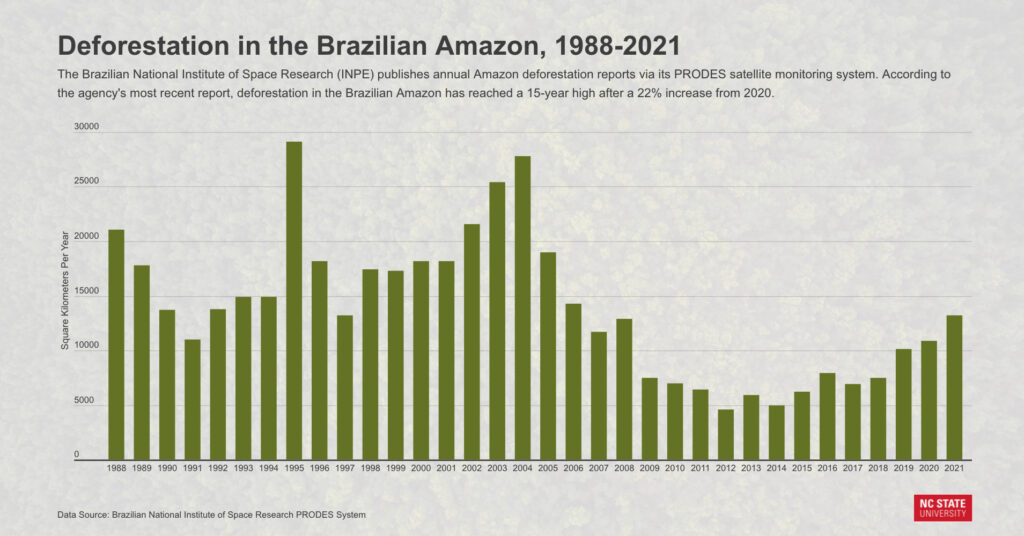

Unfortunately, the Amazon is under increasing threat from human activities, particularly deforestation in the nearly 2 million square miles of it located in Brazil. In fact, between August 2020 and July 2021, deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon hit the highest annual level in 15 years at 5,110 square miles, an area 13 times the size of New York City.

The primary driver of deforestation in the Amazon is demand for agricultural land, mostly for cattle ranching and soy production, according to Erin Sills, Edwin F. Conger professor of forest economics and head of the Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources at NC State.

Sills, who is also a research associate for the Amazon Institute of People and the Environment, said farmers and ranchers often cut down and burn trees throughout the rainforest to clear it for crops and livestock.

“These operations are essentially feeding the world’s appetite for beef, and to a lesser extent, milk and leather,” Sills said.

Many scientists who study the Amazon fear the rainforest could soon reach a point of no return where it starts to dry up, severely compromising its ability to absorb and store carbon dioxide. It’s currently estimated that the Amazon contains about 123 billion tons of carbon above and below ground.

When the Amazon’s trees are cut down or burnt, that stored carbon is released into the atmosphere and amplifies the Earth’s natural greenhouse effect, causing the atmosphere to trap more and more heat. This process ultimately leads to global warming.

Unfortunately, as a result of deforestation, the Amazon is already emitting more carbon than it absorbs. This trend raises the question of whether it’s too late to save the rainforest, especially given that efforts to do so have been countered by the policies of Brazil’s president Jair Bolsonaro.

Since taking office in 2019, Bolsonaro has become well known for his disregard of environmental regulations. He’s not only dismantled Brazil’s environmental law enforcement agency, but he’s also relaxed environmental fines and voiced support for opening the Amazon to increased agricultural and mining operations.

Bolsonaro insists he’s committed to protecting the Amazon, however. In fact, he was among the more than 100 world leaders to recently sign a pledge to end deforestation at the 26th annual United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow, Scotland.

The pledge from Brazil has been met with skepticism, with scientists and advocates questioning its validity. Some have even labeled the move as greenwashing— a commitment intended to promote Brazil as being environmentally-friendly without enacting meaningful change.

“Brazil’s agreement to end deforestation doesn’t reflect the reality of what’s happening on the ground,” Sills said. “Bolsonaro’s administration continues to undo years and years of work that previously reduced deforestation in the Amazon. It’s really been quite startling.”

In 2004, the Brazilian federal government reformed its forest laws, adopting a wide range of new regulations and policies aimed at stopping deforestation in the Amazon while promoting sustainable economic development. Consequently, Brazil reduced its deforestation rates in the rainforest by 84% over the span of eight years.

Bolsonaro’s policies have since contributed to increased deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Fortunately, though, both non-governmental organizations and state governments in the rainforest continue to work to identify low-deforestation development options, according to Sills.

“Brazil’s agreement to end deforestation doesn’t reflect the reality of what’s happening on the ground.”

Additionally, all of the state governments in the Brazilian Amazon are also now engaging with the Lowering Emissions by Accelerating Forest Finance (LEAF) Coalition and Architecture for REDD+ Transactions (ART), both of which aim to incentivize public-private efforts to reduce deforestation.

“There are a lot of people working to reduce deforestation in the Amazon, so I have to believe it’s not too late to save it,” Sills said.

It remains unclear, however, how the COP26 pledge will ultimately affect rainforests like the Amazon, as it depends on whether signatory countries pursue a zero deforestation or net zero deforestation strategy, according to Sills.

While a zero deforestation strategy completely prohibits forested areas from being cleared or converted, a net zero deforestation strategy allows for the clearance or conversion of forests in an area as long as an equal area is replanted elsewhere — a process known as reforestation.

Sills said it’s likely that many countries and other stakeholders could adopt a net zero deforestation strategy, which could effectively reduce carbon emissions but allow continued loss of biodiversity, wildlife habitat and even Indigenous territories.

“There’s a bit of a trade-off involved with net zero deforestation,” Sills said. “While it still allows for deforestation, there are areas within the Amazon that could be productively restored through reforestation. So it could possibly benefit wildlife habitat and communities in those areas.”

For the Media: If you would like to speak with Erin Sills for a story, please contact Laura Oleniacz at ljolenia@ncsu.edu or Andrew Moore at apmoore2@ncsu.edu.