Finding Floods from Space to Support Community Action

Across the United States, flood risk is underestimated, and many people experience frequent flooding despite living outside of the 100-year floodplain designated by the Federal Emergency Management Agency. To make matters worse, 21 states lack flood disclosure laws, which require home sellers to notify prospective buyers about past flood damage.

In Reidsville, Georgia, one of the nondisclosure states, homeowner Jackie Jones learned only after purchasing her house that heavy rainfall meant substantial and costly flooding––and not only of her property but many others’ nearby. Yet, when she brought her concerns to the local city council, her observations were dismissed.

To secure the extra evidence she needed to prompt flood control action in her community, Jones turned to the American Geophysical Union’s Thriving Earth Exchange, which finds scientists to partner with community groups. Over the past year, she worked with a research team led by faculty fellow Mirela Tulbure at NC State’s Center for Geospatial Analytics, to corroborate Reidsville residents’ observations using remote sensing.

“Ms. Jackie had already collected data on whose properties flooded and the days that there was rain,” explains Geospatial Analytics Ph.D. candidate Mollie Gaines, one of Tulbure’s advisees. “As the team of remote sensing scientists for this project, our goal was to determine how we could best use satellite imagery to validate the lived experiences of rainy day flooding reported by the residents of Reidsville and Collins, Georgia.”

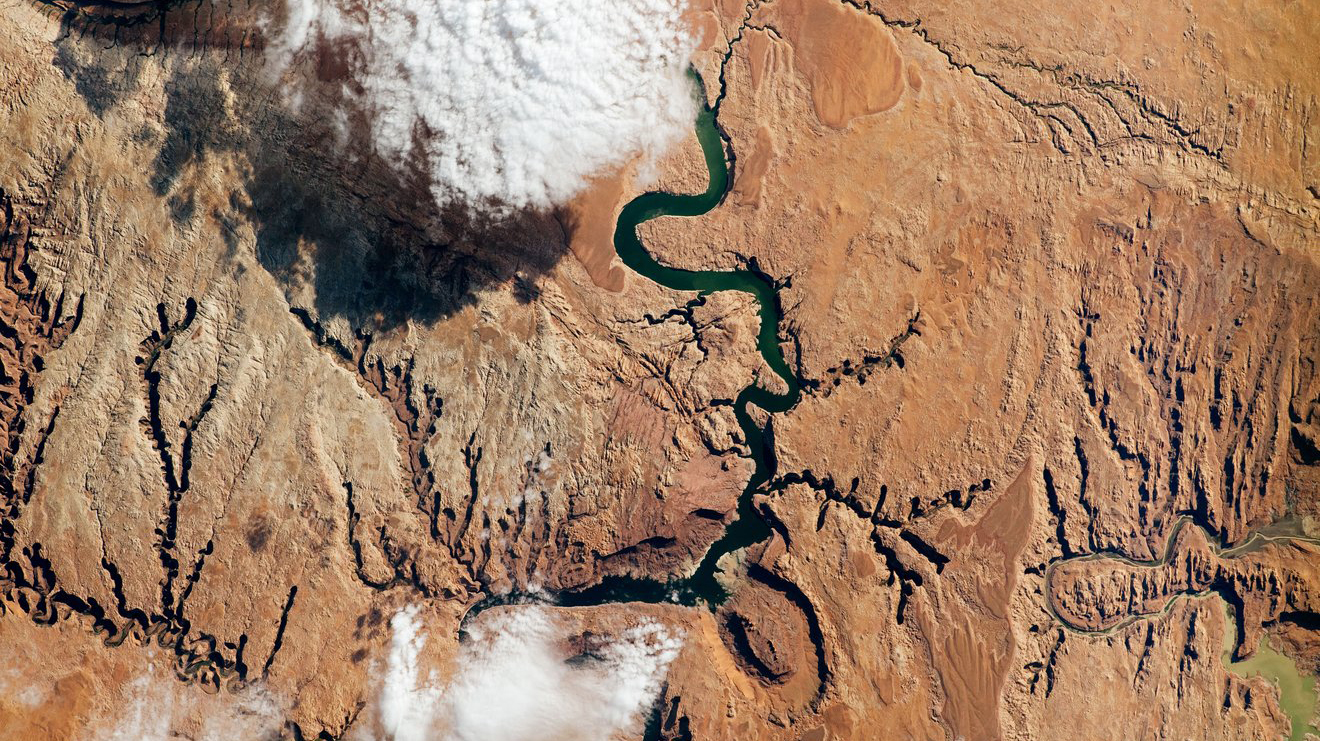

Spotting a flood from space is not as straightforward as it may seem.

“When you’re using satellite imagery to find flooding in the backyards and front yards of people’s homes, resolution is a problem,” explains Geospatial Analytics Ph.D. student Varun Tiwari, also a member of Tulbure’s lab. “Even three-meter resolution isn’t enough to capture flooding in someone’s yard.”

“Shadows from clouds, trees and buildings can also look like water in satellite imagery,” adds Gaines, making flood delineation with visual imagery tricky.

So, the research team tested different methods that could reveal changes in the proportion of water before and after reported flood events, based on the kind and amount of light reflected or absorbed in individual pixels.

“There are different spectral bands that you can get from the satellite data,” Tiwari explains, “like RGB––red, green, blue, which we can see––and NIR, near-infrared, which we cannot see.” Vegetation, urban development and water are characterized by distinct spectral signatures, and “you can have different spectral signatures in different proportions in a pixel.”

With the spectral signature for water as their focus, the research team compared satellite imagery before and after the dates of floods reported by the Reidsville community, and found that after reported flood events, the contribution of water to particular pixels increased considerably.

“We can’t say there was a flood for sure, just from the satellite data,” says Tulbure, because image resolution and shadows make flooding hard to actually see, “but we can tell there was more water in the satellite data after the reported flood event, and more rainfall from rainfall data. Corroborating these pieces of information, we can safely conclude that those were flood events.”

At monthly meetings with Jones, Tulbure’s team shared their progress and findings, with a main goal of being as useful as possible. “It was important to learn how our work would be most beneficial,” Tulbure says, “asking ‘What do you need at the end? What would be helpful?’”

Research that makes a difference

Ultimately, the team’s final products included a brief technical report, which can be included in community proposals for infrastructure projects, and a publicly accessible, interactive storymap that details the project’s findings and can be easily shared by Jones and her collaborators.

“Ms. Jackie is an invaluable resource for describing the flooding problem and the community needs,” Gaines says, underscoring “just how much effort she has put into the community science projects and how much she continues to put in.” Jones has been working with a number of groups, including the Army Corps of Engineers, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and the Anthropocene Alliance, to advance green flood-control projects. Although her work for justice continues, Center researchers are gratified to have played a part.

“This was a good experience for me, but it was great to have the students involved,” Tulbure says, “to have them see, ‘our work is impactful, it’s important, it has an immediate use.’ Students are excited about the impact––not just publishing papers, but seeing how their work will be used, really helping a community get the resources that they need.”

Before coming to NC State, Tiwari worked for five years as a remote sensing and geoinformation analyst with the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, an intergovernmental organization based in Nepal. In this role, he collaborated closely with the Afghanistan Ministry of Agriculture, gaining first-hand experience with stakeholders and communities. “When you work on a real-world problem, it makes a lot of sense, as data often represent meaningful and physical characteristics that we aim to mathematically model ,” he says, “and you have end-users who are going to use that research. You’re making a contribution, to make a change.”

“This was my first experience being one of the expert scientists on a community project,” Gaines says. “It was really cool, getting to apply our science, getting on-the-ground input, getting out of the ivory tower, and doing work that can actually benefit people. This kind of experience is exactly why I came to NC State. I’m not interested in an academic career. I’m interested in applying science to real issues, whether in government or in industry. And that is what this [Geospatial Analytics Ph.D.] program is geared toward. It is really satisfying to do this kind of work as a student.”

Additional members of Tulbure’s lab who assisted with the project were doctoral student Vini Perin, who graduated in December 2022, and undergraduate researcher Brooke Cox, who helped with the storymap. The researchers also thank Thriving Earth Exchange partners Cathy Liebowitz, Jackie Jones and Jonathan A. Sullivan.