Fall Colors and Climate Change: How Rising Temperatures Might Shift Colorado’s Season of Gold

Editor’s note: Each semester, students in the Geospatial Analytics Ph.D. program can apply for a Geospatial Analytics Travel Award that supports research travel or presentations at conferences. The following is a guest post by travel award winner Nicole Inglis as part of the Student Travel series.

Every autumn, millions of people gravitate to Colorado’s Rocky Mountains to experience a fall color spectacular. Tourists and locals alike revel in a landscape splashed with gold, and take long drives on winding roads that tunnel through forests of deep yellows and reds.

But researchers say that climate change is forcing tree distributions to change across North America, which means that fall colors may be shifting too. Aspen trees (Populus tremuloides), which constitute much of the fall color spectacle in the Rocky Mountains, are expected to move upward in elevation and northward in latitude seeking cool temperatures and moist soils.

What does this mean for fall color viewing along Colorado’s Scenic Byways, and the tourism economies that depend on this ephemeral, enchanting phenomenon?

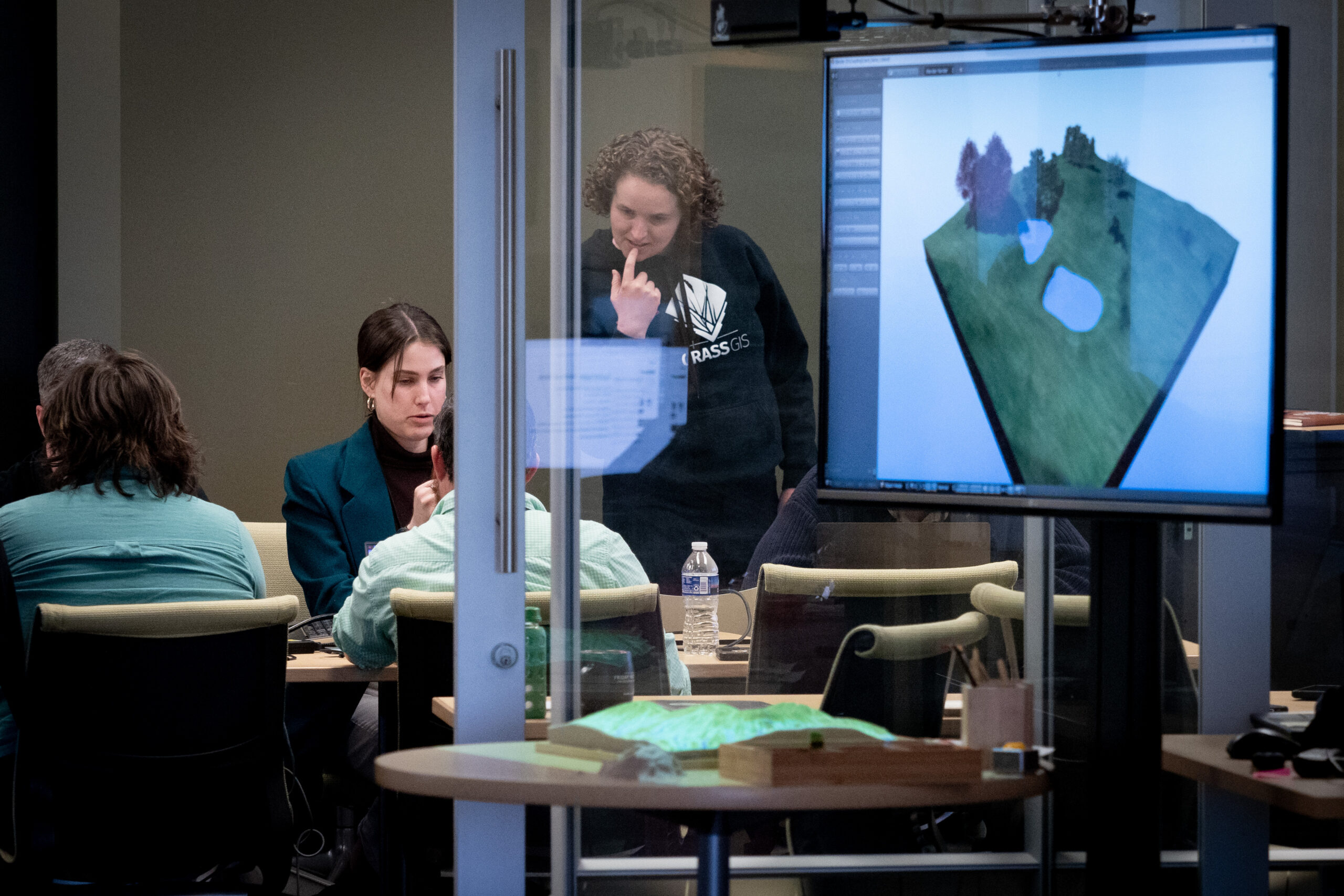

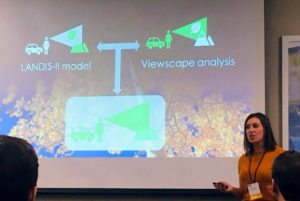

Center for Geospatial Analytics faculty fellow Jelena Vukomanovic and I set out to answer this question by integrating two geospatial models. One model simulated the ecological process: where aspen trees might grow over the next 100 years. We used LANDIS-II, a forest succession model developed by center faculty fellow Rob Scheller. The second model explored the human dimension: specifically, what areas of the landscape can be seen from designated scenic byways on Colorado’s Front Range. This is called a “viewscape” model. And the heart of this project lies at the nexus of these two models––where landscape change meets visibility.

We found that aspens are likely to decline over the next 100 years in Boulder and Larimer counties, and that climate warming, with or without drought, will exacerbate this decline. Under warming conditions, aspen are also more likely to occur at higher elevations than if the temperature were to remain the same. All of these changes, however, might not be seen by roadside leaf peepers: our analyses suggest that while aspen will decrease within our studied viewscapes, more dramatic declines caused by climate warming will occur elsewhere on the landscape, not within view of visitors to scenic byways.

Why? Remarkably, these particular roads occur where surrounding visible landscapes fall within a range of topographical and climatic conditions (elevation, average temperature, angle to the sun, etc.) that protect aspen from the effects of warming.

Ultimately then, landscapes visible from roads frequented by tourists may not reflect the true impacts of climate change––a valuable lesson that what we can easily see does not necessarily tell the full story of what is happening.

Thanks to funds provided by the Center for Geospatial Analytics Travel Award, I presented preliminary results of this research at the annual meeting of the North American chapter of the International Association for Landscape Ecology in April 2019. In the talk, entitled “Scenic Drives and Fall Color Viewing in Colorado Impacted by Changes to Quaking Aspen Distribution Due to Climate Change,” I shared early findings from this project, and why we think these patterns emerged.

After the presentation at IALE-North America, I shared in some illuminating discussions with colleagues from around the country about how wildfire haze might be affecting visibility from scenic drives and how the timing of leaf color change is also an important consideration for tourism-based economies.

Conversations about climate change often emphasize ecological impacts. With this research, we want to ensure the conversation includes the cultural resources that forest landscapes provide, such as their scenic beauty, tourism value and contribution to the fundamental character and identity of the landscape.

Integrating these two geospatial models––where the aspens are moving and what humans can see––offers a powerful lens for envisioning future landscapes, which can help communities plan for a sustainable future.

Find the presentation slides on my GitHub site.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my advisor Jelena Vukomanovic for her expertise and guidance and the Center for Geospatial Analytics for supporting conference travel.

- Categories: