No Trees at Sea

Amid the domestic turmoil and Motown sounds of the mid-1960s, a group of NC State forestry graduates set sail across the Atlantic and Pacific oceans as members of a secretive research project. It was an exhilarating period in our lives as we sought to complete an objective that proved to be more important than we could have ever imagined.

By the time my classmates and I graduated with our bachelor’s degrees in forest management in 1967, the Cold War and Vietnam War had made it difficult for recent graduates to find employment. But the federal government, through the U.S. Civil Service Commission, had begun hiring students with strong educational backgrounds in science and mathematics. And it was paying a premium salary because of the cost of living in Washington, D.C.

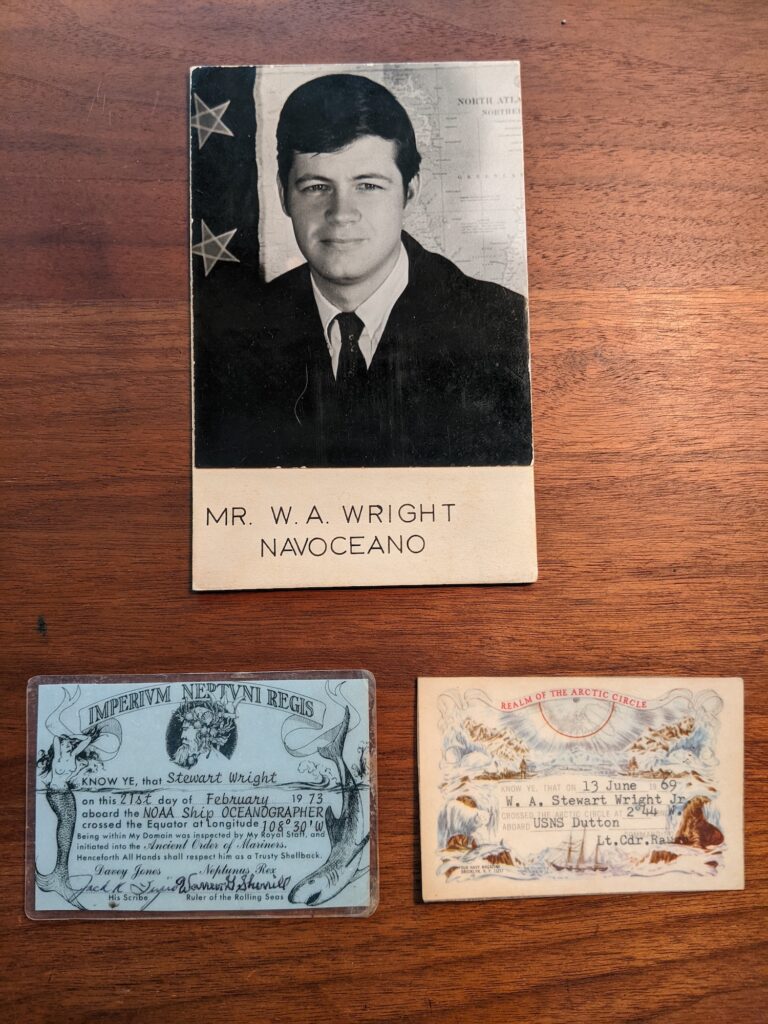

It wasn’t long after graduation that I, along with Ben Schwanda, Ken Johnson, Scott McKeller and Les Brouillard, decided to temporarily step away from forestry to join the U.S. Naval Oceanographic Office (NAVOCEANO). Many of us were assigned to the Gravity Division as geophysicists. Les was assigned to the Hydrographic Charting Division as a nautical cartographer, joining our classmates Herb Kirk and Bill Chandler, who had been selected as the division’s interns during the summer months preceding graduation.

When we joined NAVOCEANO, we never imagined participating in research that would contribute to the direct defense of our country. The Cold War with Russia, brought on by the nuclear arms race, prompted NAVOCEANO to assign many geophysicists, including myself and my fellow NC State classmates, to sea cruises aboard WWII-era Liberty ships and newly-constructed oceanographic vessels to collect data about the ocean floor and its features.

Sea cruises, also known as SURVOPS, routinely consisted of a Military Sealift Command service crew, who operated the ship, a U.S. Naval detachment of officers and enlisted sailors, corporate technicians and civilian scientists. During these expeditions, we utilized technologies such as sonar, gravity meters and magnetometer equipment to collect raw data about the ocean. We usually spent 25-30 days at sea followed by a week of import, then back out to sea for one or two more rounds of data collection.

Much of the data captured during these voyages led to the research and publication of charts of the world’s oceans. It also allowed us to accurately map the ocean floor for the first time in history. Mountain peaks, valleys, canyons, troughs, and plains were precisely depicted in the form of numbers on large mylar sheets. Some of the early data gathering was processed on Univac (IBM) computers the size of refrigerators — a stark contrast to the digital cell phones available in today’s world.

The entire crew felt immense loyalty to the mission, knowing in their own way that their time at sea could reduce the probability of a nuclear war between the U.S. and Russia. The data that we collected allowed our country to arm its nuclear submarines and safely navigate within harm’s way of Russia. At the same time, our Poseidon nuclear missile program now had important gravity data to compensate for the drag on projectiles in order to hit targeted territories.

Our voyages did not come without challenges, however. Sea legs had to be earned and constantly tested under terrible weather conditions in the North Atlantic and Western Pacific oceans. The sea dominated control of the ship during severe winds and often created huge elevator rides up and down between large swells of water, while the constant pounding and groaning of the ship imposed fear among many in the crew.

The crew generally avoided eating meals during these dangerous times due to the lack of cooks, the taste of the food and the chance of physical harm from slipping or falling. Cream chip beef, considered a staple while at sea, allowed most of us to survive from one day to the next. But it didn’t ease the mental strain of being at sea. The long periods of separation from our family and friends proved to be challenging for many of us.

All personnel, aside from the Military Sealift Command service crew, were cleared for “secret” or “top secret” classification by the Department of Defense so we weren’t allowed to share our location or details about our assignments with family or friends. It wasn’t until the 1990s that our missions were successfully declassified by then-Vice President Al Gore as part of a broader push to utilize Cold War data for environmental research.

A 1996 article published by The New York Times predicted that our findings would advance many fields beyond environmental studies, including commercial deep oil and mineral exploration — and it was right. Much of our research has since been utilized by allied countries like England and Norway, which have prospered significantly because of major discoveries of oil in the dark waters of the North Atlantic.

Our work not only benefited our country and allies, but it also gave us purpose. I began my service aboard the USNS Dutton, a WWII-era Liberty ship, boarding the vessel in 1969 on the same dock in Belfast, Ireland where the infamous Titanic was built. During my six years of service with NAVOCEANO, I completed five tours on two other Liberty ships, including a shakedown cruise on the newly-constructed USNS Wyman, before embarking on my final voyage aboard the NOAA Oceanographer alongside naval officer groups from Peru and Chile in 1973.

It was during my final voyage as we crossed the equator that the onboard physician informed me of the death of Ken, who had remained one of my closest friends since we had joined NAVOCEANO. My other classmates lived on and found their own paths in the years following. Ben enjoyed a successful career in the forestry industry. Scott shifted his employment to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration where he rose to a top-level position in charge of a ship fleet. Les started his own real estate business in Raleigh.

As for myself, I spent three years as the chief county planner in my hometown of Denton in Caroline County, Maryland before I was encouraged to enter the banking industry. I earned a Diploma of Graduation from the Maryland Banking School in 1982 and rose to the position of regional vice president for one of the nation’s largest regional banks before retiring in 2007, though I eventually re-entered the workforce as a forester and environmental planner for Dorchester County, Maryland.

While I only spent three years with Dorchester County before the Great Recession led to budget cuts, it was the most gratifying role of my entire career. My final employment as a forester provided me with the opportunity to join the Caroline County Forestry Board, a state mandated organization, which I still have the honor of serving after 12 years. All those years spent aboard ships and at a desk were certainly meaningful, but I found true happiness in the end by returning to the forest — the very place I learned to cherish during my time at NC State.

- Categories: