Emerson Brown: Digging for Diamonds – A Museum Experience

Growing up, I spent almost every rainy Saturday with my dad at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. I am eternally grateful for these memories, and even though I gained a fear of prehistoric giant sloths, the sense of awe and curiosity the museum gave me has stuck throughout the years. So, when I got the chance to work there, I couldn’t have possibly said no.

I was hired as a Geology Research and Collections intern at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. My supervisors were two geologists: Allison Dombrowski, Geology Collections Manager, and Dr. Chris Tacker, Research Curator of Geology. This internship was through the State of NC Internship Program, which gives university students the opportunity to be involved in state government for a summer and explore the inner workings of our different state departments. I specifically worked in the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, which oversees museums, libraries, and parks all over North Carolina. My workstation was in the NC Museum of Natural Sciences Collections, which is where all of the museum’s specimens not on display are stored. When I walked in for the first time, I was blown away by how many dinosaur bones and taxidermied animals lined the shelves, including many extinct species. Most important to me, however, was the extensive collection of rocks and minerals.

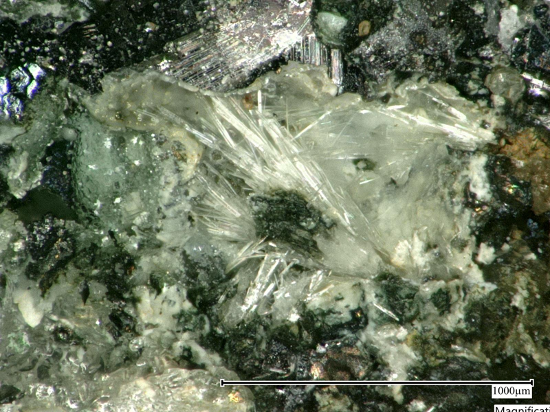

Originally, my internship was focused on specimen conservation and scientific outreach. However, I quickly realized I would also be working on a research-based geology project looking for NC diamonds and their indicator minerals, which meant that we were essentially going on a treasure hunt. I learned about lamproites and kimberlites, which are different diamond-bearing rocks classified by their formation. Lamproites are formed in high temperatures, while kimberlites are formed in low temperatures. We deduced that we were looking for a lamproite in the Western Piedmont of North Carolina, and what better way to do that than to go out there yourself?

This was one of my favorite parts of this experience. We spent many hours off-trail in the woods, cracking rocks open to see if they could potentially hold traces of that all-elusive lamproite. I also used a gold pan to sort out the denser portion of the creek sediment. Even though I left with countless bug bites on my ankles, being able to shadow these geologists taught me a lot about how this type of work is conducted. I had never done fieldwork to this extent before, so this week gave me a chance to dive into some real-world applications of the skills I have been learning about in my classes. Unfortunately, we didn’t find any diamonds out in the field, but we still have lots of rock and sediment samples to sift through back in the lab!

Less diamond-related, but still fascinating, was my main project for the collections side of the internship. This included using a tool called GEOLocate. Similar to Google Earth, GEOLocate allows the user to assign latitude and longitude to specific place names, and I found myself going over hundreds of data points, each representing the locality of a mineral that had been recently donated. Knowing where individual specimens come from allows the museum to see the breadth of its collection and to prepare for potential new exhibits. Even though it’s called the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, it’s important to have records of rocks and minerals from all over the world. You never know what you might need!

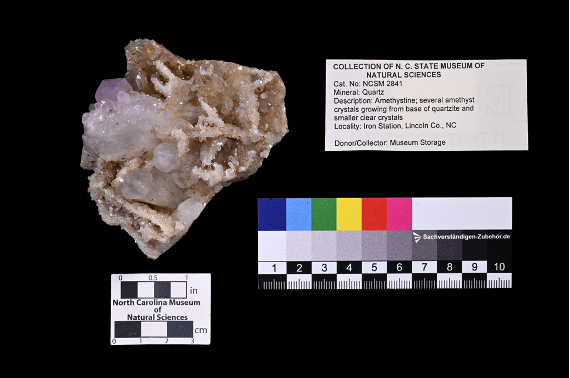

Another one of my favorite parts was taking pictures of each specimen. This is a huge ongoing project, with at least 10,000 total specimens needing to be photographed. I had never used a professional camera before, so this was a completely new skill I got to develop throughout my internship. Even though I certainly wasn’t able to finish all 10,000, I still think I got pretty good at it!

The locality data and photos will be incorporated into the museum’s collections database, which makes it easier for specimen lookups and to keep the museum’s data all in one place. The great part about this database is that it is available to the public. One thing I admire about the museum is its dedication to helping others learn about science. Because I had access to their extensive resources at a young age, the museum is directly responsible for my interest in the natural world. Their dedication to science communication and public outreach is admirable and I am extremely grateful to become a part of it.

Between my projects, I was given access to many opportunities through the State of NC Internship Program. I got to speak with many different interns in entirely different fields, and a majority of them are also NC State students! The program provided excursions to different agencies and departments within the NC government, such as a scavenger hunt at the museum and a tour at the Steve Troxler Agricultural Sciences Center. My supervisor even set up tours at the NC Museum of Art’s conservation lab, where I got to see some art restoration at work. My favorite, however, was a full-day trip to the Pine Knoll Shores Aquarium, where we had a behind-the-scenes tour of the fish tanks and the machinery that helps the aquarium run. These experiences gave me time to connect with my peers and created a well-rounded experience that I will treasure.

During this internship, I was able to gain experience doing fieldwork, conducting research, and taking care of a geology museum collection. Participating in both geology research and collections conservation gave me insight into how versatile the museum can be. I have been blown away by the positivity in the community and feel reinforced in my choice to study geology and environmental sciences. Although I am still uncertain about exactly what topics I will pursue further in my career, this internship has given me many resources to help me narrow it down. Most importantly, this experience has solidified my passion for natural resources and I am excited to see what I will do next.