Estela Garcia: My Favorite Freshwater Species’ Are the Ones with No Brain and No Eyes

If there’s one thing I know about fieldwork now, it’s that it is unpredictable and never guaranteed… And that field work is usually followed with lots of lab work!

I’m Estela Garcia, a second-year Environmental Science major with a concentration in GIS. This summer I traveled to Massachusetts to help grad students with their research on freshwater mussels along the Connecticut river through the Doris Duke Scholars Program. As an intern I worked with two graduate students from the University of Massachusetts, each grad student had a different focus but both related to research to help conserve freshwater mussel species that live in and around the Connecticut River, with a special focus on endangered species like the Brook Floater (Alasmidonta varicosa) and Yellow Lampmussel (Lampsilis cariosa). The Connecticut River is home to many species of freshwater mussels. Known as nature’s “water filters”, these freshwater mussels are vital to the river ecosystems. The project grant both students pull from is called the “Advancing Conservation and Restoration of Brook Floater and Associated Freshwater Mussels” under MassWildlife. The grant was made in efforts to aid in the conservation of these freshwater mussel species, particularly the Brook Floater. The river stretches between various states, and the focal area for the grad students was the area between Connecticut and Massachusetts where there are many old dams that are no longer in use, some that contaminate the rivers water quality. When I heard about the opportunity to be an intern for their summer research work, I was excited at the chance to get some experience working in the field and working on GIS mapping. Both already had summer technicians, so as their intern I had a lot of flexibility as to what I could help them with and focus on during the summer, which ended up including a little bit of everything and a whole lot of fish chores!

Coming in I knew very little about freshwater mussel species and had previously never done any fieldwork, but thankfully I had the chance to work at the Cronin Aquatic Resource Center, which is a research center focused on endangered freshwater mussel species, as well as floodplain conservation and climate change work under the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service. Cronin works in collaboration with the University of Massachusetts so most of the people I worked with or around had some sort of affliction with the University. Everyone was very excited and passionate about their research and very willing to help guide me through the process of creating sediment traps, working in a lab, handling mussels, caring for fish, and even driving a motorboat! I learned a lot about what the freshwater mussel life cycle looks like, especially for yellow lamp mussels, how they have adapted to ways to look like a fish to attract their hosts without having any eyes to see their host fish, or even a brain for that matter, which hands down was the coolest fact I learned all summer! As “natural filters” the freshwater mussel species use their siphons to filter through the passing water, which is important for other fish and river species. The plan for the summer was to conduct mussel surveys along the Connecticut river mainstream, and along smaller wadeable streams, assist with sonar data collection and mapping, and conduct host fish trials for Yellow Lampmussel to see if striped bass worked as a potential host fish for mussel glochidia (baby mussels). But as I mentioned previously field work doesn’t always go according to plan and this past summer Amherst Massachusetts received some of the most rainfall it has seen in years, therefore snorkel and wading fieldwork did not run through the whole summer. Fortunately, enough I did get to go out a couple of times before the rain picked up and was able to take part in a snorkel survey for mussels, which was an amazing experience that allowed me to begin familiarizing myself with freshwater mussel ID. This allowed me to later work on and complete a dichotomous key for the common freshwater mussel species for fieldwork use in semesters to come.

Though my fieldwork opportunities were limited to the first week or so of my summer I still had a lot to keep busy with back at Cronin. Once the sonar data was collected and processed it was me and the other intern and technicians’ job to use it to add on to the map of the Connecticut river using ArcGIS Pro. The tasks were tedious, and I often spent hours working on small sections, but I really enjoyed the satisfaction of finishing part of the processed data, and the experience gave good insight into what I may be working with in the future as my career.

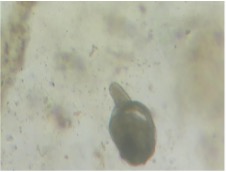

Another big aspect of the internship was the host fish trials. The trials were set to happen in August, so we spent about a month setting up and growing the fish so that they would be large enough to be potential hosts for the mussel glochidia. We used both striped bass and largemouth bass in the experiment, the largemouth bass were the control group since that species of fish is already known to be a host for yellow lampmussel. In a natural environment a mussel would use its lure to attract a fish, the lure itself would flap right above the mussel oftentimes looking like the host fishes’ prey. Then as the fish would encounter the mussel the mussel would release the glochidia and they would attach to the fish’s gills, and eventually drop off and become juveniles. We mimicked this experiment and then kept water quality and maintenance on the fish for weeks after as the glochidia began to drop off. In the lab we would use microscopes to count the individual glochia drop off to calculate the attachment rate. It was so surreal to see after a few weeks how the drop off collected became juvenile mussels (noticeable by their “foot” muscle which sticks out and allows the mussel to move around). I think seeing the baby mussels move around under the microscope, especially after dropping liquid food into the samples, had to be my favorite part of the summer because it felt like in a way, I helped raise the juvenile mussels and saw them grow up over the course of a month.

Overall, the summer internship was very eye opening to the possibilities within the conservation field and I enjoyed learning about freshwater mussels and gaining lab, field work, and fish husbandry experience. I really enjoyed being able to help with a wide variety of projects and tasks, and getting to work with others who also had a passion for conservation. Not one person I met this summer was not passionate about their work and strive to in the future find a career where I can surround myself with people who are as passionate about conservation and their work as the people, I met this summer were. Of course, the weather was a bummer, since I did really like being outside snorkeling, but it gave me a good look at the realities of fieldwork, and how dependent research is on surrounding environmental factors. I also learned that as much as I enjoyed the work, I did this summer I do not think I am equipped to constantly be working in the field due to health conditions. From here I plan to get an internship next summer where I continue to work with GIS collection and analysis and hopefully in the future I can work where I can work with GIS data for conservation efforts like I did this summer!