Historic Discrimination to Blame for Diversity Gap in US Parks, Expert Says

On the morning of May 25, 2020, Christian Cooper, a New York City resident and avid birder, entered a semi-wild area of Central Park known as the Ramble in search of red-bellied woodpeckers and other migratory songbirds.

But as Cooper was birding, he was startled by a woman shouting at her unleashed dog. Cooper, a Black man, politely asked the woman to leash her dog in accordance with the area’s rules. When she refused, he began recording a video with his phone.

In the video, the white woman shouts at Cooper that she’s going to tell the police that “an African-American man is threatening my life” before dialing 911.

The video, which Cooper’s sister posted on Twitter following the incident, ultimately resulted in the woman being charged with filing a false police report and losing her job. But it’s also since inspired an ongoing public discourse about the enduring racism people of color face in outdoor spaces across the United States.

“If you connect the dots throughout history, it becomes extremely clear that people of color in America have been systematically excluded from nature,” said KangJae “Jerry” Lee, a professor of parks, recreation and tourism management at NC State.

Research shows that people of color are drastically underrepresented in outdoor recreation, with recent data showing that only 23% of visitors to the 419 national parks across the U.S. are people of color.

Lee, whose research focuses on the relationship between race and ethnicity and leisure participation, said the lack of diversity in outdoor recreation is largely a result of historic discrimination in America’s public parks.

In a manuscript published in the journal Social and Cultural Geography, Lee and his co-authors, including NC State’s Myron Floyd, examined structural patterns of injustice in the creation and history of public parks in the U.S.

“Our research shows just how persistently American parks have been defined, conceptualized and managed by powerful white elites who were racists and eugenicists,” Lee said. “They defined nature as something that only white individuals can access, experience and appreciate.”

Lee said the actions of these individuals ultimately comprise a larger structural pattern known as “slow violence” — a slow but consistent and pervasive form of violence exercised by the powerful to oppress and marginalize others.

A History Rooted in Injustice

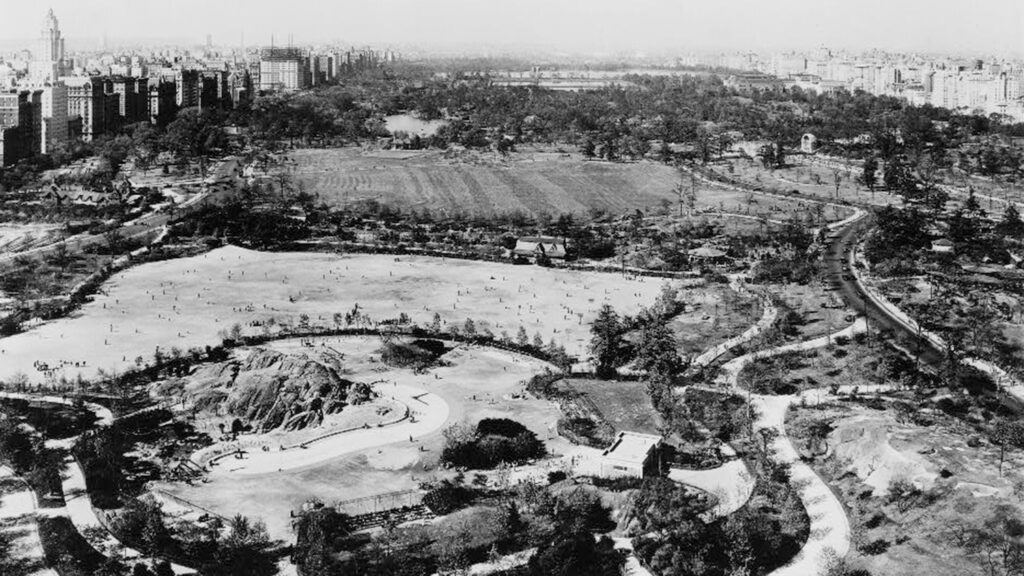

The history of slow violence in America’s parks can be traced back to the very first park itself — Central Park in New York City, which according to Lee, was initiated by wealthy and powerful white businessmen, newspaper editors and political leaders.

During the 1840s, these individuals lobbied for the development of Central Park, claiming it to be a solution for beautifying the city amid population growth and deteriorating conditions. Their true intentions, however, were much more sinister.

Lee said the city’s social elites, most of whom were majority landowners, actually wanted to develop Central Park because they hoped it would raise their property values and create a recreation space for middle- and upper-class white families, all the while displacing Black residents and German and Irish immigrants.

Unfortunately, because the people who initiated Central Park were politically and socially involved at both the city and state level, its development was approved in 1853. The construction of the park began four years later, displacing thousands of residents living in a majority-Black settlement named Seneca Village.

“Seneca Village was one of the few places that Black residents in New York State were able to own property at the time,” Lee said. “Its destruction took away their voting rights because the state required Black men to own at least $250 in property and hold residency for at least three years to be able to vote.”

To make matters worse, according to Lee, the city entered into one of its worst economic depressions just as park construction began. And the displaced Black residents from Seneca Village couldn’t find employment following the destruction of their homes despite having been promised construction jobs at Central Park.

Central Park was ultimately constructed by an all-white workforce and completed in 1858, according to Lee. The park’s development, however, continued to impact the city’s minority and immigrant communities even once it was finished.

In fact, because the city constructed Central Park between the Upper West and Upper East Sides of Manhattan, it became nearly inaccessible for working-class and immigrant communities located in the outskirts of the city, depriving them of the many mental and physical health benefits provided by urban greenspaces.

Lee said, “A lot of the injustices we see happening in outdoor spaces today actually began over a century ago in Central Park. It marked the start of gentrification and the displacement of communities of color to build parks for the white middle and upper class.”

The Spread of Slow Violence

In 1872, more than a decade after the creation of Central Park, President Ulysses S. Grant signed into law the creation of Yellowstone National Park — a first for the U.S. and the world — “for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.”

However, like Central Park, Yellowstone National Park wasn’t created for all people, according to Lee. In fact, the creation of national parks in the U.S. was led by white elites who held imperialistic, xenophobic and racist views.

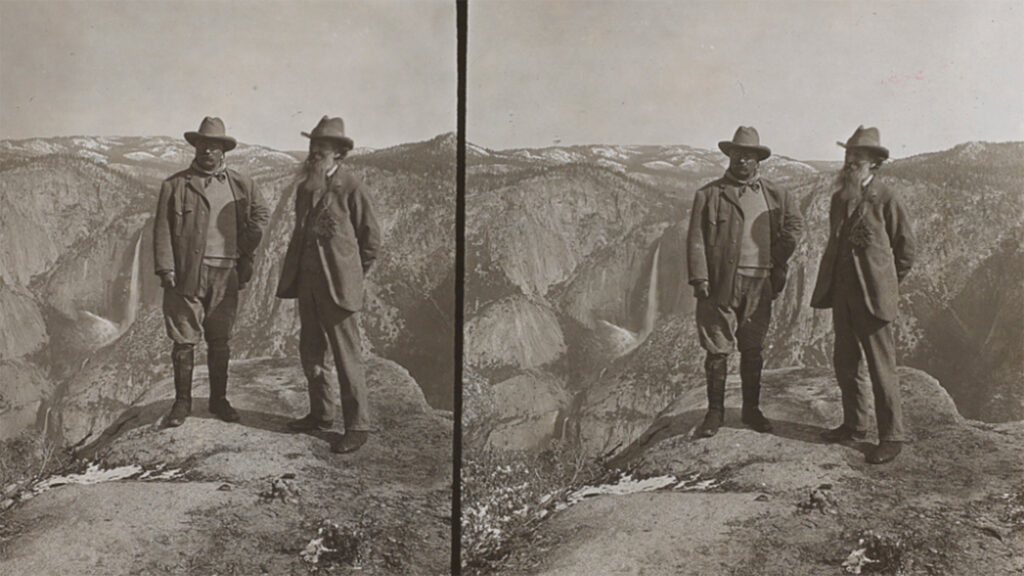

These individuals — including Madison Grant, Theodore Roosevelt and John Muir — feared that white Americans would lose social dominance and considered the preservation of nature, which included the creation of national parks, as a means of maintaining white supremacy, according to Lee.

“In response to urban expansion, white elites promoted this idea that cities were dirty places inhabited by immigrants and people of color and that natural spaces were clean, quiet places that white people should enjoy because they can develop certain characteristics that make them a more competitive race,” Lee said.

Muir, the first president of the Sierra Club who is considered to be the “father of the National Parks” due to his role in the creation of Yosemite and Sequoia national parks, claimed that Indigenous people “seemed to have no right place in the landscape” despite having lived there for thousands of years.

Along with Roosevelt, who established many national parks, Muir also often used derogatory language when describing Indigenous people in his writings and supported removing them from their ancestral homelands.

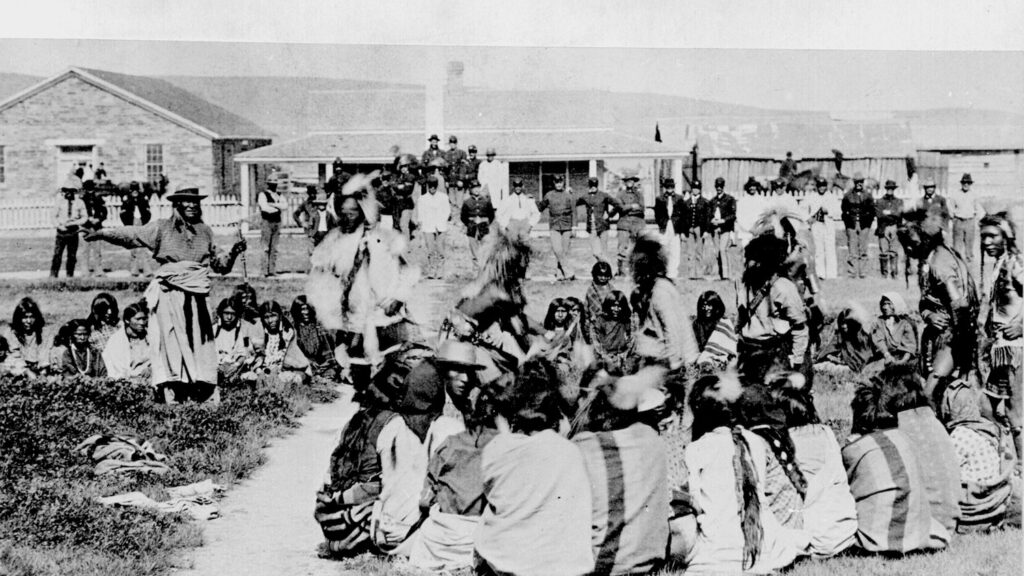

Lee said these ideas — combined with the influence of ideologies such as colonialism and manifest destiny — ultimately culminated in the U.S. government conducting an “ethnic cleansing” to create many national parks. In fact, the military often forcibly relocated Indigenous people to reservations, resulting in countless deaths and the loss of civilizations and cultures.

By the time President Woodrow Wilson founded the National Park Service in 1916, the Department of Interior oversaw 14 national parks and most Indigenous people lived on reservations where they were considered wards of the government.

“The government committed genocide against Indigenous populations to create an American identity through the outdoors. But they took more than just their lands,” Lee said. “Everything they had cultivated for centuries was suddenly gone.”

Slow violence didn’t stop at the creation of national parks, however. Jim Crow laws and customs, for example, barred Black Americans from many state and national parks across the south. They had to instead use either “Negro areas” adjacent to White parks or parks built only for Black people, acccording to Lee.

In 1952, Black Americans had access to only 12 of the 180 state parks across nine southern states, according to Lee. That included North Carolina’s Reedy Creek State Park, which was created in 1950. Following desegregation, Reedy Creek was combined with Crabtree Creek State Park to form William. B Umstead State Park.

Latino Americans also faced descrimination in state and national parks throughout the 20th century, according to Lee. In fact, Latino Americans were prohibited from visiting many of these parks in states like Texas, further promoting the idea that nature was something that belonged solely to white Americans.

What the Future Holds for America’s Parks

Though state and national parks are now desegregated and accessible to all Americans, the effects of slow violence continue to endure in the outdoors — evidenced by the lack of diversity among today’s park visitors.

Because their ancestors were largely prohibited from visiting public parks, many people of color across the U.S. face generational gaps in appreciation, skills, knowledge and experiences of these spaces, according to Lee.

Many people of color also avoid outdoor spaces because they fear encountering racism and violence, according to Lee, who said he sometimes feels unsafe and unwelcome in certain places when traveling because of his Asian American identity.

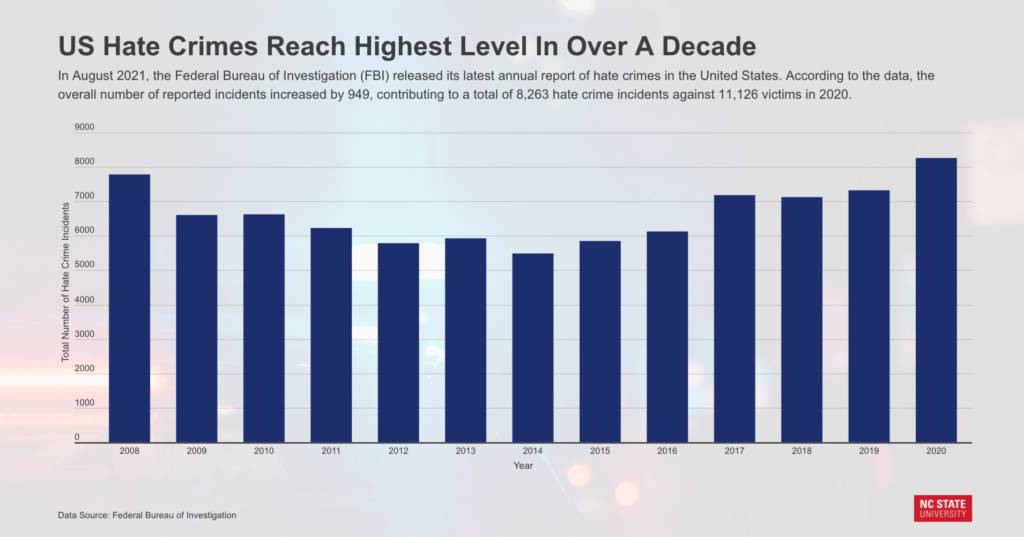

Since Cooper was falsely reported to the police in 2020, a number of racially- and ethnically-motivated hate crimes have occurred in parks and other outdoor spaces across the U.S. In fact, just last year, two elderly Korean Americans were assaulted while walking in an Orange County park in California.

Despite these incidents, many people of color participate in and enjoy outdoor recreation, which according to Lee, is crucial for society to recognize if the lack of diversity and inclusion in parks is going to be adequately addressed. It’s also crucial for society to recognize the ongoing impacts of slow violence in public parks.

“Society has to undergo a philosophical reorientation,” Lee said. “Many people think parks are trouble-free and democratic spaces where everyone is welcome. But they weren’t created with the intention of them being available to non-white individuals.”

Lee added, “We need to cultivate a greater awareness of these histories and the continued impacts of oppression. Because if we don’t add nuance to our understanding, any effort to terminate slow violence in public parks will remain superficial and ineffective. Once we accept and own these histories, we can better manage our parks for future generations.”

At the community level, Lee said municipalities should implement regulations throughout park planning and construction to not only ensure affordable housing for displaced residents but to also mitigate potential environmental impacts to communities. At the state and national levels, agencies should focus on hiring initiatives aimed at improving diversity and inclusion in leadership positions.

“Once we accept and own these histories, we can better manage our parks for future generations.”

Since its inception, the National Park Service’s leadership has been predominantly white, with Robert Stanton being the only Black individual to serve as director from 1997-2001. Last year, Charles “Chuck” Sams III, a member of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation in Oregon, was sworn in as director, becoming the first Indigenous individual to lead the federal agency.

“It’s important that we see people of color in the decision-making process because it combats the racial stereotype that nature is only for white people,” Lee said. “It’s also critical in terms of resource allocation and organizational culture. They can allocate resources to create new programs and hiring practices that promote inclusion and equity.”

Social movements also play an important role in combating the idea that outdoor recreation is only for white people, according to Lee. The Cooper incident, for example, led to the creation of Black Birders Week. And nonprofits, such as Outdoor Afro, Latino Outdoors and Indigenous Girls Hike, continue to promote diversity and inclusion in outdoor spaces across the country.

“A lot of positive social changes are happening. But there’s still a lot of work that needs to be done to ensure equitable access to our country’s outdoor spaces,” Lee said. “If we don’t manage these movements wisely, we might go backwards.”

This post was originally published in College of Natural Resources News.

- Categories: