This NC State Researcher Wants to Disaster-Proof Your Home. Here’s Why.

NC State’s David Tilotta knows firsthand the destruction caused by natural disasters.

In the spring of 1997, Tilotta, then a professor at the University of North Dakota in Grand Forks, was forced to evacuate his home — alongside 50,000 other residents — as the nearby Red River flooded the city and its surrounding communities.

The flood, which was triggered by an abnormal thaw of snow and ice following a winter that featured above-normal snowfall across the Northern Plains, ultimately caused about $2 billion in damages to infrastructure throughout Grand Forks.

Once the flood waters receded, Tilotta returned to the city to find that his home was still standing. However, as he inspected the interior, Tilotta discovered his finished basement submerged in at least seven feet of water.

“It was an eye-opening experience,” Tilotta said. “I learned a lot about remediation and rebuilding, and in the process, I decided to apply my background as a chemist to natural disasters … I sort of turned lemons into lemonade.”

Tilotta, whose early research focused on the analytical chemistry of environmental pollutants, expanded his research after the flood to study disaster resilience and recovery, with a focus on the chemical contamination and decontamination of construction materials.

Now a professor and extension specialist at the NC State College of Natural Resources, Tilotta is working alongside his colleagues in the Department of Forest Biomaterials to develop disaster-resilient housing materials, including engineered wood panels found in walls, floors and other structures.

“If we can understand why some housing materials fail when exposed to extreme conditions, companies can make better products that prevent homeowners from having to completely repair, replace and rebuild after a natural disaster,” Tilotta said.

A Growing Storm

Research shows that millions of homes across the United States are concentrated in areas prone to hurricanes, floods, wildfires, tornadoes and earthquakes. But according to Tilotta, many of today’s homes aren’t equipped to withstand natural disasters.

Additionally, many of the current U.S. infrastructure and building design standards don’t take climate change into account even though it’s expected to increase the frequency and intensity of some natural disasters — a trend that could cost homeowners billions of dollars.

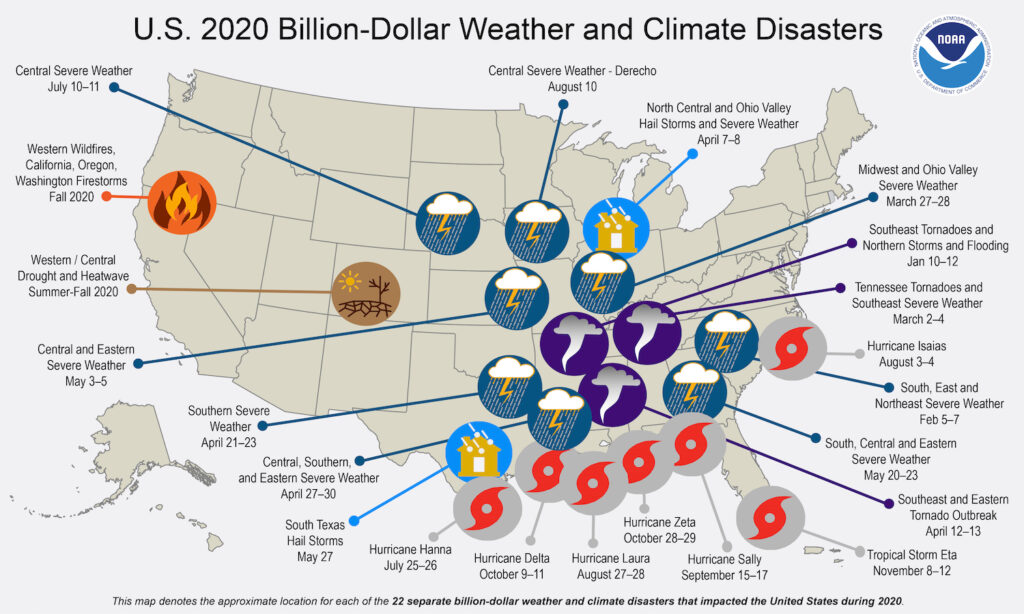

In 2020 alone, the U.S. experienced a record-breaking 22 billion-dollar natural disasters, with the events costing the nation a combined total of $95 billion in damage. The previous record for billion-dollar disasters was 16 in 2011 and 2017.

With the increasing prevalence and cost of natural disasters, architects and builders are adopting new technologies and materials that can withstand such events. Homeowners, however, remain hesitant to adopt disaster resilience, according to Tilotta.

“Everytime a natural disaster occurs, we learn from it and make changes to design and building codes. So we are seeing improvements,” Tilotta said. “Unfortunately, people don’t want to invest much in their homes with respect to natural disaster resilience. It usually takes them staring at a tornado across the street to realize they need to do something … it’s just human nature.”

Tilotta added that previous surveys of homeowners across the southeastern U.S., conducted as part of the Department of Homeland Security’s Resilient Home Program, found that most participants would rather invest their money in a home theater room instead of implementing disaster-resilience measures throughout their homes.

Launched in 2008, the Resilient Home Program was a multi-phase study composed of members from NC State, Savannah River National Laboratory, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Clemson University, Tuskegee University, Oak Ridge National Laboratory and various other institutions and agencies.

As the program’s lead researcher at NC State, Tilotta worked with other faculty members to develop online resources about the tools and technologies available for disaster resilience and recovery, as well as performance-based guidelines to encourage construction of buildings to better withstand natural disasters.

“Many people are unaware of the things that need to be done to a home to make it more resilient to natural disasters, so one of our goals was to educate them,” Tilotta said. “But as we found out through the surveys, education isn’t always effective because people don’t see a tangible benefit to upgrading their homes.”

The Future of Housing

Though the Resilient Home Program is no longer active, Tilotta continues to study the resilience of construction materials against extreme weather conditions. He and his colleagues are currently examining how resistant oriented strand board panels are to floodwater, for example.

Oriented strand board is a type of engineered wood panel that’s used extensively in subflooring, single-layer flooring, wall and roof sheathing, mezzanine decks and even furniture, according to APA – The Engineered Wood Association.

Construction materials, especially engineered products made from oriented strand board, can crumble or lose structural integrity when exposed to water, according to Tilotta. Unfortunately, flooding is expected to intensify in both urban and coastal areas across the country as climate change causes more frequent periods of heavy and prolonged rainfall, making the U.S. housing stock increasingly vulnerable to damage.

“A lot of the engineered wood products on the market right now aren’t designed to withstand flooding, but there isn’t a deep understanding of how these products fail under various flood scenarios,” Tilotta said. “We really want to know how long these products retain their strength properties when exposed to water because that will help to determine when homeowners need to replace them.”

In Hodges Laboratory, Tilotta and his team previously submerged 4×8 boards of various oriented strand board products in 30-gallon tanks that contained river water or saltwater, allowing them to simulate the effects of both inland and coastal flooding. Some of the samples were also exposed to tanks containing oil in order to simulate the effects of contaminated water.

After soaking the boards for a couple of weeks and then drying them out, Tilotta and his team conducted mechanical testing to see how well the samples meet performance standards like weight-bearing capacity.

Tilotta also recruited the help of Phil Mitchell, a wood products extension specialist and associate professor in the Department of Forest Biomaterials, to conduct a statistical analysis of each test to validate the results.

“We conducted mechanical testing on hundreds of samples, and no two boards break the same,” Tilotta said. “That’s why statistical analysis is an important part of this research. It gives us confidence in our results.”

Preliminary results show that the strength properties of engineered wood products are different after being soaked in saltwater versus freshwater, according to Tilotta. So far, however, many of the tested samples have failed to withstand flooding conditions, likely a result of the glue joints rupturing as the wood expands and contracts when exposed to water.

Going forward, Tilotta said he plans to apply chemicals and physical modifications to samples in an effort to identify a cost-effective additive that maintains the strength of engineered wood products against floodwater.

- Categories: